Selecting A Tool For Inventory & Assessment

June 30, 2015

Perhaps because archives generally deal with unique materials, the internal thinking tends to be that their needs for collection management are unique — particular to the scope of the collection and to the history and character of the institution. Not that I entirely disagree with this. Whereas things like ISBNs and Library of Congress Call Numbers, for example, work splendidly for published materials and lending libraries, that kind of centralized identification system does not make sense for original and singular manuscripts, oral histories, etc, and therefore archives establish their own identification and arrangement system, naming conventions, and other practices that may be more codified in other situations.

An exception which proves the rule here is the cataloging of audio and video materials. Even with published works, public libraries will create a local system of identifiers and organization, the same way those relics we called video stores did. Descriptive metadata can be force fed into a MARC record, but even with published works the results can be less than satisfactory.

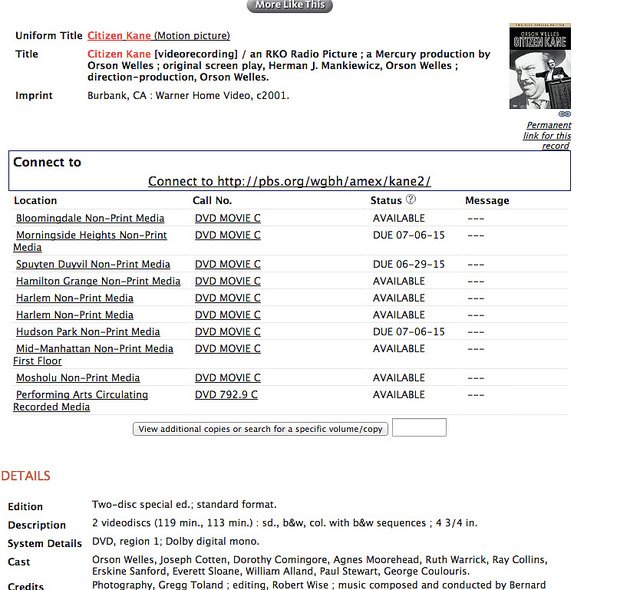

As we see here in an example from the NYPL catalog (which I’m only using because they are my local library, not to chide them), most of the branch libraries holding Citizen Kane give it the call number DVD Movie C, suggesting their DVDs are just arranged in alphabetical order regardless of genre, director, actor, era, or other differentiating information. There are no doubt barcodes on the items to manage circulation of the items and the disc should be easily findable if shelved correctly, but, by no means an uncommon situation, the intellectual arrangement is rudimentary and does not reflect an understanding of the cinematic arts.

This has been the lot of audiovisual collections in most libraries and archives. The traditional sciences of library science have not consistently addressed the management of media collections. In that way, things like cataloging, the creation of finding aids, and other methods of gaining intellectual control over collections has had to be largely local in nature, because one may often end up forcing audiovisual records into a manuscript/book rubric or have to make up some methodology on they fly.

Of course, due to this, one problem that seems to occur a lot in the archival field is a constant reinventing of the wheel to develop utilities or tools to assist in the work of describing and managing collections. And we at AVPreserve are guilty of that, too (or actually, I think it’s just me…), developing different systems for doing assessment and inventory work, often scrapping earlier work and starting from scratch. In part we do this as part of the constant refinement and (hopefully) improvement of our utilities, creating something that is functional to start but then iterating as we learn and as use cases are more well defined. In part, though, it is the old conundrum of every collection being unique and requiring a unique approach.

Whatta ya gonna do?

Well, what we have done is try to create tools that are structured enough to be useful and provide solid, transferable data, but flexible enough to adjust to collections that span multiple formats, multiple sources, multiple storage histories, multiple production histories, and multiple et ceteras. The primary tools we use for documenting and analyzing collections are MediaScore and MediaRivers (developed with Indiana University), our Catalyst Inventory tool, and our new AVCC Inventory tool.

What’s the difference, and which one would you choose, you may ask? Well, the simple answer is, it depends on your collection and what you want to do!

The slightly less simple answer is it depends on if you want to collect asset information at a higher level or at the item level, what kind of resources you have to take on a project (staffing, budgets, equipment, computing infrastructure), the expertise you have available to collect the information, and the timeline you are on.

For the more detailed answer, well, check out this spreadsheet that compares the requirements and features of the three tools. Are you looking to try and gain better intellectual control over your audiovisual collections? To plan and prioritize for a digitization project? Or just simply try to figure out the extent of what you have so you can start making some noise about it to attract funding? One of our approaches might do the trick for you. So check ’em out, or, you know, build something new.