Article

AVPreserve President Chris Lacinak Elected To AMIA Board

8 October 2013

Congratulations to AVPreserve Founder and President Chris Lacinak upon his election to the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA) Board of Directors. The Board meets regularly to help “ensure that AMIA’s mission is fulfilled and to provide strategic leadership to move the association forward”. Chris is a long-time member of AMIA, regularly presenting at the Annual Conference and contributing to various committees, as well as the audiovisual preservation knowledge base overall. His two-year term will begin at next month’s conference in Richmond, VA, where he looks forward to being even more involved as a participant in directing the continuing development of the field and the resources needed to do our work. Congrats as well to Tom Regal (Director of the Board), Jacqueline Stewart (Director of the Board), and Caroline Frick (President of the Board) on their selections as well.

AVPreserve Collaborates On First AMIA Hack Day

2 October 2013

The 2013 Association of Moving Image Archivists Annual Meeting will feature the first ever Digital Library Federation/AMIA Hack Day to take place on November 6th in Richmond, Virginia. Along with co-conspirators Lauren Sorensen (Bay Area Video Coalition) and Steven Villereal (University of Virginia), AVPreserve Senior Consultant Kara Van Malssen is helping to organize the event.

Hack Days are designed to provide a collaborative workspace where people with different skill sets can come together to develop technological solutions to specific problems in a condensed amount of time. The AMIA event will be a unique opportunity for practitioners and managers of digital audiovisual collections to join with developers and engineers for an intense day of collaboration to develop practical solutions around digital audiovisual preservation and access.

To be successful these events require the input of people who care for collections in addition to people with strong technical and programming skills. There is a lot of room to explore and create in the area of digital video preservation, so we hope you’ll come help! The event is free, and further information can be found on the AMIA / DLF Hack day Registration Form. See you in Richmond!

AVPreserve Celebrates Archives Week

1 October 2013

October 6th-12th marks the 25th annual Archives Week in New York City, a celebration of the richness and diversity of archival collections across the Metropolitan region. The Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York is a major supporter of the event and, as usual, has helped organize a number of open houses, lectures, workshops and behind-the-scenes tours of archives throughout the city — all of which are free and open to the public.

AVPreserve is pleased to be a part of the festivities, both as attendees and participants. Kicking things off, Senior Consultant Joshua Ranger will be presenting at the Disaster Preparedness Symposium taking place at the Center for Jewish History on October 7th. Josh will be talking about the importance of metadata and documentation for disaster preparedness and recovery, both in cases of catastrophic loss and loss of institutional knowledge. The presentation will cover several case studies of AVPreserve projects, including the Eyebeam recovery effort after Hurricane Sandy and the inventory of the NJN Public Television collection after the station closed. The panel will also feature talks from Laura McCann and Rachel Searcy (NYU Libraries), Shae A. Trewin (The Image Permanence Institute), and Martin Tzanev (WITNESS).

Later in the week is the NYART Awards Ceremony, honoring the work of archivists and those who support archival programs. AVPreserve President Chris Lacinak has been a part of the group organizing this event, which will present awards to Rhizome (Innovative use of Archives), New York Archives Conference (Outstanding Support of Archives), Peter Wosh (Archival Achievement), and the Brooklyn Historical Society (Educational Use of Archives). Congratulations to all of the winners!

And finally, AVPreserve and METRO will (finally) release the first episode of the archives podcast “More Podcast, Less Process”. This first iteration features Don Mennerich (NYPL) and Mark Matienzo (Yale) discussing digital forensics and other aspects of caring for born digital collections. Look for the official release next week, and go visit your local archive or historical society!

Watching Movies In A Theatre Is Not Always Watching Movies

6 September 2013

Thanks to Luke McKernan’s Picturegoing blog for inspiring this post.

For those who have met me after I moved to New York it may be surprising to hear that one of the things I was most excited about when moving here was the cinemas. Except for the brief college years when campus repertory was an option, I had always lived in places where we had to wait weeks (or months) for some movies to come to town, and independent or foreign cinema was relegated to whatever Miramax decided to release out of their hoarding vaults. But now, now I was going to get to see everything the first week of its oscar-baiting or platformed release, in addition to whatever oddity or re-release hit the theatre for a day or week.

My first weekend in town not taken up with moving was Labor Day weekend, and I plotted a multi-theatre extravaganza for that Monday, including The Aristocrats, Broken Flowers, and Grizzly Man. And to boot, I was fitting everything in before 5:00. Matinee tickets all around, yo.

But in a shocking blow to my fond memories of beating the system when picturegoing (see also: how long can I pretend I’m 12 years old?) I discovered that most NYC movie theatres do not have matinee pricing, and I shelled out 13 bucks for each flick. Having just studied the 19th century dramatic genre of plays dealing with the corrupting influence of cities I should have been more prepared, but, man, New York steals your innocence fast…Probably because they charge more for doing so.

***

From that point on through attending theatres with too-small screens and seats of questionably cleanliness, movies that sell out five hours in advance, and dealing with long time cinephiles who stand above you staring and breathing loudly as they try to figure out what to do because you have sat in “their” seat, my New York cinema experience was — if authentic — not what I had grown up loving about going to the movies. And the going is an important differentiation here. It wasn’t necessarily about the films themselves (I could watch Beastmaster at home just about any time and be happy), but something about the process of going to the cinema and the feeling around it. Being a young man of limited means in a small town, this almost exclusively meant matinees and double features. How else would I also have money for that box of stale Red Vines it would take me hours to gnaw through? And except for the odd drive-in, it also exclusively meant multiplex viewing…If four screens counts as multi. (Like I says, small town.)

As a result of this I mainly watched movies during the day in mostly empty theatres (unless four people actually does count as empty) for the finest PG and PG-13 comedies of the 1980s, and also got to see some accidentally avant-garde double feature pairings. An early one I recall was Snow White (back during the rise of home video when Disney still had a regular-ish re-rerelease schedule for their animated films) and the fear-computers-as-much-as-the-Soviets classic War Games. (Theme: Eh, kids will like both of these.)

The perfect convergence of the empty theatre and double feature came with Big Top Pee-Wee and Short Circuit 2. (Theme: Nobody is watching these, so let’s free up a screen for something else.). The vivid memory I have isn’t anything from the movies themselves, but standing to buy my Mambas and Dr. Pepper and then hearing a loud, sustained laugh coming from the theatre. I thought I was late and someone was already enjoying that hilarious robot’s antics, so I rushed inside. Turns out the room was completely empty. The previews had started, and the booming laughter was from a trailer for the Tom Hanks/Sally Fields film Punchline, a trailer which was merely audio of a single person laughing for an extended period combined with an image and some text.

***

One of the things I grapple with frequently as a media archivist is the issue of how we engage with media, and how that impacts the preservation and presentation of materials. It has begun to gel for me in a way that this engagement is one of constant change, change that is both imperceptible and mired in nostalgia.

Not imperceptible immediately, but over time as we get used to change and forget those shifts. The same way when you see a child every day and do not notice changes in height or maturity as you would if you only saw that child once a year. I think about something like newspaper design. Every Sunday I read the Times Magazine, and every so often they change the fonts, column spacing, and other layout designs. At first those changes are jarring, and I’m not so sure I like them because it seems so much harder to read, but after a few weeks I get used to it and forget what the old design was even like.

But mired in nostalgia because of external experiential factors that surround our engagement. In the case of the Times Magazine, I may not remember articles, but I get out-of-sorts if I miss that quiet, lazy weekend morning with a cup of coffee. For me personally that nostalgia of cinema is not film versus digital or big screen versus small screen, but that feeling of indulgence and slight surreptitiousness: watching not particularly great movies in the middle of the day (or middle of the night), mostly alone, with something delicious to imbibe. Perhaps this even goes back to my original engagement with films, which was on television, and frequently involved me pretending to be sick so I could stay home from school and watch Universal Horror or Godzilla movies.

Picturegoing in New York has never hit this particular treat bar, but the toy train hobby of my adulthood has recreated it — sitting down on a Saturday afternoon with a glass of whisk(e)y and some B-movie or foreign action film on DVD or streaming. I don’t disagree that it would be a different (and perhaps better) visual and aural experience projected in a theatre, but being on the East Coast now, the theatre would probably sell mushy Twizzlers instead of Red Vines.

They just don’t make movies like they used to.

— Joshua Ranger

AVPreserve, METRO Release Audiovisual Cataloging & Reporting Tool

4 September 2013

AVPreserve announces the Beta release of the AVCC Cataloging Tool and Reporting Modules in conjunction with The Metropolitan New York Library Council’s (METRO) Keeping Collections Project. The tool is offered as a free resource to help archives manage, preserve, and create access to their collections.

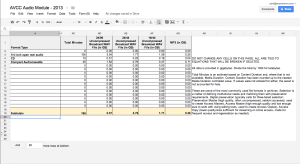

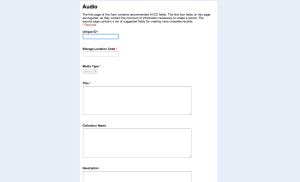

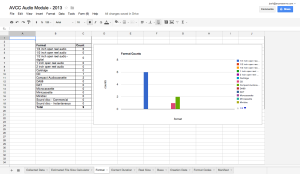

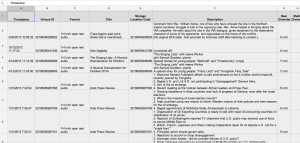

AVCC is a set of forms and guidelines developed to enable efficient item-level cataloging of audiovisual collections. Each module (Audio, Video, Film) includes individualized data entry forms and reports that quantify information such as format types, base types, target format sizes, and other data critical to prioritizing and planning preservation work with audiovisual materials.

Based on years of experience with how audiovisual collections are typically labeled and stored, AVCC establishes a minimal set of required and recommended fields for basic intellectual control that are not entirely dependent on playback and labeling, along with deeper descriptive fields that can be enhanced as content becomes accessible. The focus of of AVCC is two-fold: to uncover hidden collections via record creation and to support preservation reformatting in order to enable access to the content itself.

More information and a request form for access to your own module is available through the METRO Keeping Collections website at http://keepingcollections.org/avcc-cataloging-toolkit/. AVCC is currently in Beta form and has been designed in Google Docs. Currently only the Audio and Video modules are available. The development of a more stable web-based database utility is anticipated in early 2014, and your feedback in testing this current version will help. Please direct any questions to AVPreserve Senior Consultant Josh Ranger via the AVCC or avpreserve.com contact forms.

AVCC was developed by AudioVisual Preservation Solutions with support from The Metropolitan New York Library Council (METRO) Keeping Collections project. Keeping Collections was launched to ensure the sustainability and accessibility of New York State’s archival collections as part of the New York State Archives Documentary Heritage Program. Keeping Collections provides a variety of free and affordable services to any not-for-profit organization in the metropolitan New York area that collects, maintains, and provides access to archival materials.AVCC is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA.AVCC ©2013 AudioVisual Preservation Solutions, Inc.

AVPreserve Releases Interstitial – Free Error Detection Tool

3 September 2013

AVPreserve is pleased to announce the release of interstitial, a new tool designed to detect dropped samples in audio digitization processes. These dropped samples are caused by fleeting interruptions in the hardware/software pipeline on a digital audio workstation. The Interstitial tool Follows up on our work with the Federal Agencies Digitization Guidelines Initiative (FADGI) to define and study the issue of Audio Interstitial Errors.

interstitial compares two streams of digitized audio captured to a digital audio workstation and a secondary reference device. Irregularities that appear in the workstation stream and not in the other point to issues like Interstitial Errors that relate to samples lost when writing to disc. This utility will greatly decrease post-digitization quality control time and help further research on this problem.

interstitial is a free tool available for download via GitHub. Visit our Tools page for this and other free resources.

Toward Less Precious Cataloging

9 August 2013

For a number of years after college I was in the workers compensation and general liability industry, bouncing around among positions from file clerk to claims adjuster to data analyst. Somewhere in there I did transcriptions of phone interviews between adjusters and claimants. One of the more depressing parts of the job, I tried to distract myself by attempting to transcribe things as faithfully as possible, reflecting every single er, uhm, stutter, pause, and garbled sentence fragment. I wanted to reflect how people really spoke in all of its confusion and banal glory.

Also, coming out of literary studies, I forced myself to imagine there was some meaning to those various tics and patterns, but I also wanted to see how far I could stretch the plasticity of punctuation. What length of pause was a comma, a dash, a double (or triple!) dash, an elipsis? Are fragmented thoughts governed by semi-colons even if such marking was unintended by the speaker? One almost has to feel (or, at least I do) that under copyright law my expression of this recorded speech was so transformative that those transcriptions were wholly new works of art!

Did I mention I was very bored at this job?

It is true, however, that transcription is an art. It is the interpretation of information in one medium into another, not necessarily compatible, medium. I guess it wouldn’t be considered a fine art because it is more along the lines of didacticism — the direct communication of that information with maximal understanding as a goal, rather than an approach of impressionism, nuance, and open questions of interpretation.

But an art it is, requiring specialized knowledge to be done well and skill greater than just typing the words as they come. One can look at the frequent mistakes of spell check and speech-to-text, and consider the complex set of rules structured around such utilities, to appreciate how difficult written language is, in spite of our false sense of security in the rules of grammar. The ability of a text to be read by a machine does not confer infallibility and comprehension to that machine — on its own or as a conduit to a user. Despite Strunk & White’s efforts, there was a reason they wrote of elements of style.

*********************************

I find cataloging and related record creation to follow along these same lines. It too is a system of communicating information that is more of an art than its (multiple) rules based structures may suggest. It is also a system in which the art and stylistic traditions can and do fail machine readability, even when specifically designed for such.

You see, part of the art of cataloging is a series of visual tropes or signifiers that denote concepts or avenues of interpretation. For instance, [bracketed text]. This typically does not mean that there are actual brackets in whatever text, but rather may mean “This is an unofficial value I made the decision to assign to this field”…or maybe “I couldn’t read the handwriting and this is my guess”…or maybe “This is commentary, not actual information from the object”. Likewise brackets may be used to contain text such as […] or [?], which could mean “Unintelligible”, or “Maybe?”, or “Just guessin’ here”. (That last is my own way of sayin’ it.) One sees this frequently with titles, dates, and duration especially, though such visual signifiers may appear anywhere in a record.

And these markings are a thing of beauty — poetic layers of expression in six line strokes. A toehold of information in an uncertain world. A reflection of the cataloger’s fidelity to truth, even when it means admitting the truth is unknown and that one has failed in identifying it.

But.

But.

But, as at times can be the case, such art is impractical, limiting the efficiency of working with large data sets, or the advantage of machine readability to cleanup and search data, or the achievement of goals associated with minimal processing, which for archives is often the first pass at record creation.

As I have argued before, the outcomes of processing legacy audiovisual collections should support planning for reformatting and for collection management. This mean creating records at or near item level. This means data points like format, duration, creation date, physical characteristics, asset type, and content type must be quantified to some degrees. This means no uncertainties. There must be some kind of value for planning and analysis to work, whether it is an estimate or a guess or yeah-that’s-wrong-but-things-will-come-out-in-the-wash — or whether we just use common sense and context to support our assumptions rather than undermining them. This means be less precious.

The diacritics of uncertainty are meaningful, but when analyzing data sets they can push segments of records aside into other groupings when they likely shouldn’t be, and they make it difficult or impossible to properly tally data for planning and selection. A bracketed number or number with text in the same field is not a number to a machine. It cannot be summed. An irregular date cannot be easily parsed and grouped within a range. A name or term with a question mark is a different value than that same term with the question mark.

We know all of this — it is why we have controlled vocabularies and syntactical rules, and why we fret about selecting the “right” metadata schema. There is much theory around archival practice that comes down to exactness and authenticity of objects and documentation. However, there is a division in how such things are expressed and understood by a computer and by the human mind. There is also a division in exactness as data and exactness as a compulsive behavior. And any exactness is laid to waste by the reality of how collections are created.

When processing for reformatting, it must be kept in mind that the data created is not the record of record. It is a step to a complete record. It can be revised when content is watchable, or when embedded technical metadata gives us exact values like with duration. We know we are wrong or uncertain. The machine does not need to know it, cannot know it. But that fact will be apparent enough to future generations over time, as it is in so many other areas.

— Joshua Ranger

AVPreserve Second Lining It To SAA 2013

8 August 2013

AVPreserve Senior Consultant Joshua Ranger and Digital & Metadata Preservation Specialist Alex Duryee will be attending the Society of American Archivists 2013 Annual Meeting in New Orleans next week.

Josh will be presenting on the panel “Streamlining Processing of Audiovisual Collections” (Session 309) on Friday morning along with expert colleagues from the Library of Congress and UCLA. He will be discussing approaches AVPreserve uses in processing collections and performing assessments as outlined in his white paper “What’s Your Product”, as well as the AVCC and Catalyst tools we have developed to support efficient inventory creation.

Alex will be presenting in Tuesday’s Research Forum “Foundations and Innovations” on the topic of compiling and providing access to large sets of email correspondence.

We’re excited to be contributing as members of SAA this year and look forward to seeing friends old and new. We love to chat about media archiving, so look for us and stop and talk — it will be too hot to do anything else in NOLA. And oh yeah, buttons

New Tools In Development At AVPreserve

10 July 2013

AVPreserve is in the finishing phases of development for a number of new digital preservation tools that we’re excited to release in the near future.

Fixity: Fixity is a utility for the documentation and regular review of checksums of stored files. Fixity scans a folder or directory, creating a database of the files, locations, and checksums contained within. The review utility then runs through the directory and compares results against the stored database in order to assess any changes. Rather than reporting a simple pass/fail of a directory or checksum change, Fixity emails a report to the user documenting flagged items along with the reason for a flag, such as that a file has been moved to a new location in the directory, has been edited, or has failed a checksum comparison for other reasons. Supplementing tools like BagIt that review files at points of exchange, when run regularly Fixity becomes a powerful tool for monitoring digital files in repositories, servers, and other long-term storage locations.

Interstitial Error Utility: Following up on our definition and further study of the issue of Audio Interstitial Errors (report recently published on the FADGI website), AVPreserve has been working on a tool to automatically find dropped sample errors in digitized audio files. Prior to this, an engineer would have to use reporting tools such as those in WaveLab that flag irregular seeming points in the audio signal and then manually review each one to determine if the report was true or false. These reports can produce 100s of flags, the majority of which are not true errors, greatly increasing the QC time. The Interstitial Error Utility compares two streams of the digitized audio captured on separate devices. Irregularities that appear in one stream and not in the other point to issues like Interstitial Errors that relate to samples lost when writing to disc. This utility will greatly decrease quality control time and help us further our research on this problem.

AVCC: Thanks to the beta testing of our friends at the University of Georgia our AVCC cataloging tool should be ready for an initial public release in the coming months. AVCC provides a simple template for documenting audio, video, and film collections, breaking the approach down into a granular record set with recommendations for minimal capture and more complex capture. The record set focuses on technical aspects of the audiovisual object with the understanding that materials in collections are often inaccessible and have limited descriptive annotations. The data entered then feeds into automated reports that support planning for preservation prioritization, storage, and reformatting. The initial release of AVCC is based in Google Docs integrated with Excel, but we are in discussions to develop the tool into a much more robust web-based utility that will, likewise, be free and open to the public.

Watch our Twitter and Facebook feeds for more developments as we get ready to release these tools!

AVPreserve At NYAC 2013

30 May 2013

AVPreserve President Chris Lacinak will be chairing a panel at the upcoming New York Archives Conference to be held June 5th-7th in Brookville, New York. NYAC provides an opportunity for archivists, records managers, and other collection caretakers from across the state to further their education, see what their colleagues are doing, and make the personal connections that are becoming ever more important to collaborate and look for opportunities to combine efforts. We’re pleased to see that this year’s meeting is co-sponsored by the Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York, another in their critical efforts to support archivists and collections in New York City and beyond.

Chris will be the chair for the Archiving Complex Digital Artworks panel with the presenters Ben Fino-Radin (Museum of Modern Art), Danielle Mericle (Cornell University), and Jonathan Minard (Deepspeed Media and Eyebeam Art and Technology Center). It’s hard to believe, but artists have been creating digital and web-based artworks for well over 20 years, and the constant flux in the technologies used to make and display those works has brought a critical need for new methodologies to preserve the art and the ability to access it. Ben, Danielle, and Jonathan are leading thinkers and practitioners in the field and will be discussing the fascinating projects they are involved with. We’re proud to work with them and happy their efforts are getting this exposure. We hope to see a lot of our friends and colleagues from the area in Brookville!