Article

The Elitism Of Film Preservation

10 April 2013

When I was studying some (and failing at) History as an undergrad (I don’t think the professors fully appreciated my approach of reading and interpreting historical texts as if they were literature) the full shift to the Bottom Up approach to the field was settling in. There was still time in class spent underscoring why that approach was important and why it was preferred, but I never got the sense that most students needed convincing at that point. It seemed that it was more just muscle memory spasms from the recent struggle of a paradigm shift away from a Top Down or Great Man approach.

In the old model history is told through the stories of leaders and powerful individuals (usually men) as if their decisions and actions were the primary causes or lessons to learn from. The Civil War as a story of politicians and generals, of singular accounts of hubris and honor, of a speech or a bit of blind luck or ill fortune that affected one man and turned the tide of battle. In the new model this is flipped over to view history as the story of the masses, of the underprivileged and commonplace as equal to the privileged and extraordinary. To continue our example, this method is well represented by the popular The Valley of the Shadow project that presents the Civil War as a story of everyday life, of soldiers and their families and their neighbors, of the farms and towns impacted by the war.

I was thinking about this topic after reading about Martin Scorsese’s recent National Endowment for the Humanities Jefferson Lecture where he spoke about the importance of film preservation. Despite his nominally Bottom Up supporting statements that all films should be preserved regardless of their box office results (the home movie and amateur circuits thank you, sir!) I came away with the distinct feeling that this was very much a Great Man view of media history. It seemed that the focus was on auteurism and Hollywood or otherwise distributed films. Or, Films.

To me this smacks of a hierarchical view of the moving image, one where Cinema is at the top, deserving of the most respect, the most resources, and the most concentrated effort (regardless of how much money it generated in release, of course). Though admittedly this would seem to include shorts, early cinema, and the avant garde — film productions influential on feature films if not of the genre itself — the summary of the speech does not seem to address the masses of amateurish and video productions that are out there (though I’m sure some people would group those two categories together…).

This bothers me in part because, despite a sympathy to the concept of the auteur’s vision, I am also too well aware of the huge amount of collaboration and serendipity that goes into film production, and a focus on the periodic or limited output of directors (or any specific creative/technical position) denigrates the roles of others in that process. It also bothers me because, despite the good work the National Film Preservation Foundation has done, their model and funding mission does not match the world of moving image collections as I experience them on the ground.

I do not see single films that require weeks of detailed work to restore them and garner front page articles in the newspaper. I see piles of U-matics and 1/2 inch open reel and miniDVs — thousands and thousands of them that need quality transfers, but are in a volume and state that would not be feasible at the same time and cost factor as a film preservation project. These are broadcast programs, interviews, field footage, news gathering, home videos, amateur image capture, production materials, and beyond. Box office doesn’t matter because there is no box office here. The auteur does not matter because these materials are more reflective of an institution or of related content produced over years and decades. It’s about the democratization and the speed that video capture enables, which also means that it’s about volume and long term impressions, not singularity and pristine objects.

Perhaps my anger is misdirected, because the frustration here is that video does not have the same foundational and federal support as film, whereas, arguably, video (and audio) is the much greater documentarian of history and culture of the past 30 years, documenting home life, political events, disasters, community, performing arts, and all degree of personal, regional, and national experiences.

I’m reminded of a project several years ago where we were discussing with the client the massive appeal/obsession with World War II footage and the relative lack of interest in more recent military events such as Grenada, Panama, Desert Storm, military response to natural disasters, etc. We lamented the fact that people were willing to let historical documents fade and decay because they were not sexy or “historical” enough, which, honestly is likely related to their nearness in time as much as the fact that recent events are on video while the Past is on film. The video was seen as less precious and less endangered (though if you want to find a Hi-8 PAL deck for me we can review that assessment).

Lest I misdirect you, this is not an argument over the comparative merits of film versus video. Both exist. Both must be cared for in the way that is best for them. Rather, it is an argument about historiography, about how we write, read, and interpret history. About the need to recognize now — not 200 years down the road — that history is currently being recorded on ugly formats in ugly ways with an entire lack of beauty and skill. Such is the human condition. Such is what we are tasked to care for.

********

Coda: But really, my biggest beef here is that Marty proclaims we should Save Everything. I mean, doesn’t he read my blog! Come on!

— Joshua Ranger

Preservation Of Audiotape & The Dolby Noise Reduction System

19 March 2013

An online introduction to the concepts and application of Dolby Noise Reduction. Misapplication of noise reduction can have a highly deleterious effect on the quality and integrity of audio recordings, thus an understanding of the system and use of the correct Dolby settings during playback and reformatting is extremely important to preservation. Includes audio examples illustrating the differences.

AVPreserve At 2013 New England Archivists Conference

18 March 2013

AVPreserve founder and president Chris Lacinak will be attending the Spring 2013 New England Archivists Conference to be held March 21st-23rd at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts. This year’s conference marks the 40th anniversary of the NEA, and the focus of the program will be on “creative, unique, and/or unexpected collaborations within and across institutional boundaries.”

One of our founding principles is maintaining active participation in the library, archives, and museum communities, continuing the growth of our knowledge and resources along with our colleagues. Regional conferences like NEA offer a great opportunity to engage and connect, and we look forward to the many interesting panels later this week. Be sure to say hi to Chris if you’re attending!

In Defense Of Unemotional Archiving

14 March 2013

When I found the joys of second hand shopping in high school it was a godsend to an oddbird in a smalltown. The act of discovery and its cheapness at that point (Huck Finn and a novelization of Saturday Night Fever for a nickel? Yes, thank you!) fueled a desire to search for something, a desire that was not well funded, to say the least. Finding those treasures pre-Internet felt special; that I could walk away with Herb Alpert, Dark Side of the Moon, Faulkner, Vonnegut, and a pair of plaid pants for under 10 bucks made me feel like I had a place in the world.

Once I was well into the game, however, I began to notice an odd reaction. Whenever I would find an album or book that I particularly liked but already owned, I felt a wave of pleasure that made me want to buy that item again. “Oh, that’s so good,” I thought, “I should snag that up.” In essence, it became less and less about the content and more and more about the high of discovery and purchase.

Luckily I was never that mentally unbalanced that I actually did stock up on duplicate copies, but that urge disturbed me. What if I had not had the self control to stop and just acquired whatever made me feel good?

Either out of lack of money or a move to cities where thrift stores were overpriced and picked over, I stopped that behavior and that kind of consumerism. Whatever the case, I saw it as an issue that I felt I needed to monitor, well before getting into the archival field.

On a personal level, I was concerned with the over-estimation of the value of the object — both aesthetic and monetary. A recent post at the AV Club covers similar territory, discussing a danger in fetishizing vinyl albums, specifically, and I too have written about the problem of the totemic object and archives. It seems fairly uncontroversial to me to say that aestheticism, nostalgia, and enslavement to process easily cloud the mind and inhibit pragmatic decision making.

The problem is, of course, that archives generally have to think on the institutional level. Decisions need to be made on large sets of materials and are impacted/influenced by various considerations around budgets, strategies, institutional priorities, and institutional politics. But the problem with this is the content of archives can often be very personal, personal in nature and of personal importance to caretakers, researchers, and users. As many people have pointed out, there is great power in the emotional connection to that content and potential advocacy in harnessing that emotional connection. However there is a conflict between that personal, emotional connection and the necessary dispassion of certain collection management decisions.

I would agree that, yes, there is a benefit in utilizing or promoting the emotional connect we have with history and historical materials. However from my point of view that is a limited benefit. Without continued prompting, emotions fade. Quickly. This is why public broadcasting, charities, museums, universities, etc. seem to be in constant outreach mode.

Not only do emotions fade, but so does their efficacy. I think of this as the Fallacy of the Big Bird Argument. I remember that it used to be that when public broadcasting was under fire they would trot Big Bird or Elmo or someone over to Congress to testify and the news would be full of stories about how it would be heartless to take Sesame Street from our children. At some point that seemed to stop happening, I suspect because at some point that refrain became empty, some mix of crying wolf and people becoming inured to the repetition.

Another issue I see is that there is limited follow through on emotional arguments. It’s very easy to get people to agree that preservation (or whatever) is important, but to get people to do something about it is a different story. In some cases this is a social issue — the degree to which people believe they should donate, volunteer, etc. — but in other cases it is because administrators, foundations, and granting agencies want harder arguments — dollars, timelines, outcomes — if they are going to get behind a project. The emotional argument is a stepping stone, a foot in the door, but it is not the endgame.

There are also two concerns here I have with how we use and talk about collections. First, especially as an audiovisual archivist, I am extremely wary about how people use sound and images to generate or project emotions onto content that abuses the integrity of the original. This may occur by reading emotion or context into an image that is false, or through something like the Kuleshov Effect. This theory states that through juxtaposition you can create false emotion, one famous example being Hitchcock’s discussion on showing an old man staring and cutting to an image of a baby versus cutting to a woman in a bikini and how that gives the viewer a different sense of what the man is thinking.

My other concern is the prevalence of the urge or advice to Tell Your Story, either by utilizing archival materials or, for archivists, talking about their collection as a form of advocacy. I’m not against story telling (otherwise I wouldn’t blog like this) but I fear the over reliance on this strategy and the over creation / over estimation of stories and their efficacy in the larger world. My original educational background is actually in early American literature — specifically the period before photography and before the writing got good. Poe, Hawthorne, and (regrettably) Fennimore Cooper are merely pretenders. This means I studied almost entirely personal narrative. Captivity narratives, conversion narratives, spiritual narratives, slave narratives, discovery narratives, epistolaries, etc… There was a ton of it being written back then, each with the idea that their story would instruct and inform others. I had very few friends to discuss these readings with because, honestly, most people hate that writing. And honestly, most of it was not very good. The pleasure was not in the story, but mostly in the history of why and how it was written and where that intersected with what was going on in the larger world.

Ultimately, I suppose, my final arguments are personal, emotional reactions to archival materials and how they are used.

Crap.

Can I start over?

— Joshua Ranger

Consultant Seth Anderson’s Personal Digital Archiving 2013 Presentation

26 February 2013

Thanks to the folks at the Personal Digital Archiving Conference 2013 (and the Internet Archive), here is the video of AV Preserve Consultant Seth Anderson‘s presentation, “Protecting the Personal Narrative: An Assessment of Archival Practice’s Place in Personal Digital Archiving”. Synopsis and original link for other playback options below.

Synopsis: The archival community struggles to fit in the private process of personal digital archiving. A common recommendation is to begin preservation far upstream, introducing archival practices early into the act of personal collection. But what may the archives best intentions introduce into the act of personal collection? Entering too early into the process may place undue influence on the decisions of the collector, the what gets kept and why? Active preservation of digital personal archives is necessary for ensuring the longevity of materials, but the archives community must be aware that this may alter the personal narratives that personal archives represent.

The need for continued preservation actions in digital archiving may represent a shift in the very nature of personal archiving. Whereas physical collections could be placed in the proverbial shoebox under the bed, the increased number of digital materials and their dispersal across numerous platforms means that the locating and identification of digital materials may be a vital new characteristic to personal archiving. This paper illuminates the paradox between the private act of personal archiving and the need for action or education from the archival community.

Studies on archives relation to personal digital archiving recommend various strategies for addressing this dilemma, including early identification and collection to basic educational resources. These strategies are valuable to the field, but reveal the complications inherent in the intrusion of archival structure on the unique process of personal archiving. This paper examines and the existing literature, critiquing the potential negative outcomes that organizational influence may have on the way an individual interacts with their personal archives. It will posit if and how archives professionals can ensure a digital process analogous to personal archiving techniques of physical materials, or if this is no longer a tenable approach to personal collection in the digital era.

Link: http://archive.org/details/SethAnderson_pda2013

PDF of Slide Deck: https://www.avpreserve.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/PDA_slides_Anderson.pdf

You Need To Plan Before You Can Preserve

22 February 2013

One issue we commonly do not factor into planning projects is the time it takes to ramp up to be able to actually perform the task. Whatever it is you want to do, there’s always a lot more time needed than anticipated to plan, select, decide, communicate, arrange, or whatever it is that has to happen to make the desired activity actually occur and be completed successfully.

These types of efforts are related to the time necessary for project management that occurs during implementation. When budgeting for a grant or a preservation project, project management — the work that facilitates the work — can often be an easily discounted or underestimated factor. Emailing is a part of our normal daily routine, so it’s difficult to isolate the project specific time we take on it or other types of communication that do not seem like ‘work’. Rather, the focus is on budgeting towards the definable activities with a palpable outcome: Processing or digitization of this many items or linear feet will take this many work hours. What we can lose site of is the time to hire, train, refine processes, and other issues that are necessary but are not directly linked to outcomes.

Similar to how the development and implementation costs of open source software add a (necessary) cost to using it, the cost of managing and implementing a preservation project — if not considered ahead of time — can become a burden or blockade to the project, or can come into conflict with other existing responsibilities.

When we express the urgency of the need to reformat and preserve audiovisual materials, it is not only because of the degradation and obsolescence risks, but also because of the normal project planning and ramp up time. When we say organizations need to start reformatting now, it’s not meant to suggest that you should start popping tapes in decks tomorrow. It means the organization needs to start developing policies, making decisions, raising funds, advocating, establishing capabilities, vetting systems and vendors, etc. etc. etc.

Realistically we are looking at a 10-15 year window in which to reformat legacy audio and video materials before the issues of decay, technology loss, and expertise loss make such work either impossible or unfeasible due to the cost factors of working with severely degraded materials and limited machinery. Thinking about this window and the time it takes to plan, gather funding for work, and then actually do the work, we believe that if you are not starting the planning process within the next 5 years you must accept that a significant portion of your audiovisual collection will be completely lost, and any resources put into other activities or collection management will have been wasted.

There is no getting around the fact that reformatting must occur for audiovisual materials to be preserved and accessed, just as there is no getting around the fact that reformatting efforts take money and planning, both of which take time gather and develop. We can’t hedge our bets on the far end of that 10-15 year window and wait until the night before to cram all the work in. We need to get to work on making that work happen.

— Joshua Ranger

AV Preserve At Personal Digital Archiving 2013

15 February 2013

AV Preserve Consultant Seth Anderson will be presenting a paper at the Personal Digital Archiving Conference on Friday, February 22nd. The Personal Digital Archiving conference will provide an “opportunity for researchers and practitioners in the field of personal archiving to convene for presentations and networking…[supporting] a broad community of practitioners working to ensure long term access for various personal collections and archives” and will be held at the University of Maryland, College Park February 21st-22nd.

Seth’s paper is entitled “Protecting the Personal Narrative: Archival Practice in Personal Digital Archiving”. His talk will be addressing the effect of digital preservation tactics of the public and of traditional archives on the private act of collection or accumulation, examining proposed methods of collection and management and how these may change the nature of personal collection.

In addition to Seth there is a fascinating set of talks scheduled on the topic of personal digital archives, an issue which is reaching critical mass with the ease of content creation and speed of technological obsolescence in the digital realm. Registration is still open, and we hope you can make it hear Seth and the rest of the speakers.

Archives Don’t Matter

14 February 2013

…But Archival Environments Do

Admittedly, when I foreswore the word ‘archive’ I offered no realistic (or unrealistic) alternative. The great benefit (and the great detriment) of such philosophical arguments is that one needn’t provide conclusive answers to one’s musings — nor, apparently, first person responsibility, either.

Regardless, I have been thinking about this topic since then and have solidified some thinking here, coming to the conclusion that using or not using the word archive doesn’t matter because archives don’t matter.

Let me clarify — the concept and the role of archives matter, which I would define as the arrangement, maintenance, and provision of access to materials (roughly matching my thoughts on the processing of audiovisual collections in relation to the primary services of an archive). The entity or shape of the archive does not matter because such collections of assets exist in many forms and, I feel, are much more likely to exist in less formal or less traditional spaces than the formal academic or governmental archive.

Formal and less formal archives all fulfill their duties — arrangement, maintenance, access — to varying degrees depending on their mission and available resources. However, formal archives are not necessarily superior across all of those aspects. For example, a collection within a television news organization may rate very highly with gathering and providing access to materials because they generate the content, have the equipment for playback and editing, and value the re-use of assets such as b-roll for new content creation. Maintenance may not rate as high because frequent, timely usability is more important, and arrangement may suffer due to the high rate of circulation of materials and lack of centralized, enforced storage and borrowing policies.

Transition that same collection to a formal archive and the level of maintenance and arrangement may rise to the higher standards of professional archival practice, but access will almost certainly drop off to almost zero until reformatting and description/processing is performed because the availability of equipment and impetus for use is not the same. When that reformatting actually does happen is anyone’s guess.

I think of these two examples as the Archival Environment and the Production Environment.

Archival Environment: Purposeful and Controlled Selection, Arrangement, & Documentation

Production Environment: Idiosyncratic or Department-based Asset Management tied to Projects, Processes, & Deadlines

Both of these represent collections of materials which may in fact be referred to as Archives. However, each play distinct roles in how collections are used and taken care of. At some point it is certain that the materials in a Production Environment will need to move into an Archival Environment in order to retain their accessibility. The materials will need to be reformatted in order for the content to survive beyond degradation and technological obsolescence, and they will need to be arranged and described in a consistent, documented manner in order to be discoverable beyond the institutional knowledge of the original creator/caretaker.

Despite that being the case, Archival Environments need to adopt more from Production Environments regarding the provision of access, because most Archival Environments are failing on that point. Film, video, and audio collections are languishing in archives, too under-described to be findable and existing in formats or conditions that are not playable.

Archives don’t matter because there is a lack of trust by creators, researchers, and the public that access to collections will be provided on reasonable timescale, if at all. And this issue is about much more than speeding up processing and creating the glorified container lists that are finding aids, because that approach does nothing about solving the blockade to access that is remediated by reformatting. When dealing with audiovisual materials there is no question, no argument about it: Reformatting must happen at multiple points in the life cycle of the content because the lifespan of the content extends well beyond the technology housing it.

Archival Environments matter because they help support the longevity of discovery and access, but if that access to playable content is not provided the nominal archive is remiss in its duties. Until such time as that duty is met we cannot rightfully distinguish between or value the role of the traditional archive over the lay archive of something like a YouTube merely on the tenets of description, storage, and best practices alone.

— Joshua Ranger

Why We Shouldn’t Save Everything

6 February 2013

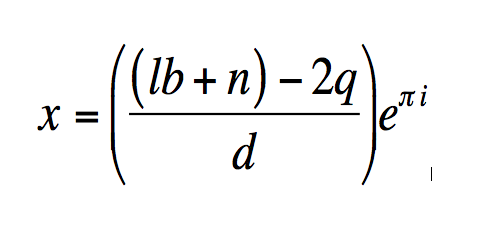

Several years ago I created an equation that calculated the advancement of a society in relation to its acquisition of archived knowledge. A positive result meant the culture was advancing, a negative that it was declining.

Where lb=Weight of Cultural Burden, n=Cultural Impact, q=Quantity, & d=Amount of Existing Detritus

I’ll take a slight pause for the audience laughter to die down. But for you non-maths-nerds out there, the gimmick was that eπ i = -1, thus the outcome of the equation would always be 0 (stasis) or a negative number (decline), primarily because the production of detritus in the culture always greatly outweighs the production of standout cultural works.

Yes, I have always been this much of a punk ass fool.

Regardless, I do believe that, though my expression may be flawed (even if it made me giggle) it holds a grain of truth. Most things are not great. Most things are not even good. This does not mean that the non-great do not deserve to be saved — each collection has its own mission and reasoning — but it does infer that, of the masses and masses of content we create, there is a steep curve measuring usefulness. This usefulness may be predicated on quality, content, source, methodology, or some other factor that makes the content valuable, representative, tangential, or research-worthy. The degree, scope, and reach of these factors vary, as does the amount of importance we place on each factor personally, locally, institutionally, and beyond.

In other words, one man’s trash….

This is really nothing new (as the use of a hoary adage suggests). Prioritization and deaccessioning are part and parcel of the archival practice. More highly valued materials receive more attention and more resources. Lower value materials receive less attention and, in some cases, are/should be discarded.

Not everything can be saved. Nor should it. Not just when judged at a valuation level, but at a level of content and institutional use.

However, because we are aware of mass losses of records of the past, we are hyper-aware (and in some cases hyper-vigilant) about losing anything in the present, about letting one film frame or slip of paper evade our acid free grasps. This extremism is wrong, because it causes fear and paralysis, or, alternately, overreaction. We can become so afraid of making a mistake in our preservation choices that we freeze up, or we can’t see beyond the cost and resources needed for an entire collection to see where we can take smaller bites, or we waste resources on inessential materials and activities at the detriment of other ones. No collections benefit as much as they could in these scenarios.

One issue I see here is the undue influence of the concept of author and manuscript, especially when it comes to audiovisual archives. In an author’s or individual’s archive there is an aura projected onto the materials — everything they touched or every revision made matters.

In an archive of easily reproducible materials there is bound to be duplication, low quality viewing copies, transfers that have no meaning beyond their role in moving from platform to platform within a production process, and content that is low/poor quality but never discarded by the creator.

(And to be honest, I personally feel that the totemic aura of the object is grossly misplaced in most cases, whether the item in question is reproducible or not.)

The question we need to look at is what role the asset plays/played in the day-to-day activity of the collection. In the case of an individual author, versions or revisions may be of value in tracking the creative process. In a production environment, versioning or dubs or rough cuts may (and do) lack such value. The review copies and rough edits that cycle around a production environment are of practical, of-the-moment value but do not necessarily mean anything to the work process — the same way multiple copies of a manuscript distributed to colleagues do not reflect unique content (unless annotated).

But really, even if that is the case, we have to ask ourselves how much is enough? We don’t know what a researcher 100 years from now will be interested in, but does that matter? What is the value of that research point versus the cost of storage and preservation? The archivist’s job, in part, is to support researchers, but also to care for the collection. Does that footnote in a maybe future dissertation warrant an investment that subtracts from the ability to provide broader care?

It may seem like it does because long-term, day-to-day collection management has no wow factor, no direct feedback, and can be difficult to communicate the value of to administrators. The researcher finding one thing, exclaiming Eureka, and expressing gratitude provides that warm, energizing feeling that one’s work has been done. It is a silver dollar found in the middle of a reseeded forest. Something to spend now instead of realizing an expansive value later.

What this issue often comes down to is making a decision for which we cannot see the long-term outcome. Short-term we can assess the potential benefits, but the risk that we were wrong often prompts inaction. Realistically, though, in the long-term our inaction is a much greater burden than any action we take. At some point in the future the burden of too many assets, or undocumented assets, of half-cared for assets, or un-reformatted assets will have to be dealt with. And at that point the costs will be greater and the options will be fewer. That is not what we should be saving for the future.

— Joshua Ranger

People — Don’t Use Rubber Bands

1 February 2013

The worst part of my job is dealing with rubber bands in collections. No exaggeration. I am not afraid to say I hate them. I absolutely detest them. That wasn’t always the case. I used to have bags of them around when I had a paper route. Always carried bunches in my pocket, futzing around with them making lark’s head knot chains or seeing how far I could shoot them across the room. Not now. Now they are abhorrent to me.

Don’t misunderstand me here. This is not like the head-slapping frustration or gentle weeping over preventable damage that most archivists feel about paper clips, staples, tape, and other joiners/adhesives. No, this is a Cronenbergian level of revulsion, of horrified disgust that creeps up from the pit of my stomach and burrows in at the back of my head to haunt me.

And rubber bands are not like metals or adhesives because, for the most part, they are not causing physical damage to the materials I work with. There are exceptions (loose film reels on cores bound by a rubber band) but mainly I see them used to group together related assets or to bind paper records to the object. Inevitably the rubber band dries out and snaps — either when slightly handled or on its own — or even just crumbles away.

It is these rubber remains that revolt me. Sometimes they still have a slight elasticity and move slowly (yet incompletely) to revert to their original size, like a dangerous creature that hasn’t noticed you yet so you freeze up and praypraypray it doesn’t see you.

Other times they just break apart, sloughing their dead particles over everything else. And whether they crumble or you pull them off, you’re left with a pile of ugh that looks like worms or maggots. You know it’s nothing, but fear it may start writhing at any moment.

And somehow — this is the worst — somehow a rubber band can both desiccate and melt, leaving a residue on things or even hardening and adhering to an object at the same time as they become dried husks. It’s unnatural, suggesting something between life and death, like the dried out bodies of potato bugs littering a garage corner.

But when I said somewhere up above (I don’t know where — use CTRL-F or something) that rubber bands generally are not causing physical damage, I did not mean that they are not causing harm. There is a great deal of damage to our intellectual knowledge and control of materials when rubber bands are used in this way. Specifically, as a stand in for labeling, documentation, or catalog records. What I typically see is that one tape (or simply a piece of paper) is labeled with descriptive information and the remaining bound tapes are unmarked or labeled as Tape 2, Tape 3, etc. Or the only content information is on papers that were once bound to the tape but that are not mixed with other tapes and papers that have separated.

This may not seem like a huge problem because, from the a paper point of view, it would seem like just a little additional time from the archivist or researcher to sort through and use contextual clues to properly arrange the papers as well as possible. But without the benefit of labeling, item level records, embedded metadata, or the sort, the identification and arrangement of audiovisual and electronic records is much more time-consuming and costly. The removal of paperclips and foldering of papers is an added cost to collection processing, but if that processing/access first requires (most likely) reformatting a video and then watching it, the level of cost and time explode.

When we imbue an object like a rubber band with implied meaning, that information is hopelessly opaque and severely impermanent.

It should be a temporary tool used for its intended purpose and not as a replacement for the detailed work of identification and description. In a way, all physical arrangement suffers from the same issue. It should not be assumed that order has any persistent, discernible meaning in and of itself outside of establishing context. It is a means of locating objects. At some point the structure of that order will dissolve, as it does with all things (not just rubber bands).

It is increasingly apparent that as creators we have the responsibility to document our work in ways that is clear and usable by us and by those in the future. Likewise, one of our responsibilities as Archivists is to choose and utilize systems and procedures that are transferable and able to be interpreted across systems and across time. We don’t know what access in the future will look like. We do know that we need to do what we can to help enable it, and I hope to god it doesn’t involve rubber bands.