Article

What you need to know about Media Asset Management

10 December 2024

While marketing strategies vary by company size or industry, they likely have one thing in common: a lot of content.

Every stage of the customer journey is powered by marketing content — from digital ads and social media posts to web pages and nurture emails. And if all the related workflows are going to run smoothly, all of the supporting assets need to be organized effectively.

That’s where media asset management comes in. Let’s take a look at this practice and how media asset management software can help teams achieve their content goals.

What is media asset management?

Media asset management (MAM) is the process of organizing assets for successful storage, retrieval, and distribution across the content lifecycle.

This includes any visual, audio, written, or interactive piece of content that supports a marketing goal. The list of possible marketing assets is long and can include:

- E-books

- Whitepapers

- Customer stories

- Reports and guides

- Infographics

- Webinars

- Explainer videos

- Product demos

- Podcasts

- And more!

In addition, all of these assets are produced with the help of many smaller creative elements, like images and graphics. The volume of these files grows exponentially…after all, one photoshoot alone can result in hundreds of images.

And if teams don’t have a centralized repository for their assets, finding a specific file requires a tedious search across shared drives, hard drives, and other devices — which can prove impossible without knowing the filename. Audio and video files can be particularly challenging to manage not only because they tend to be large but also because they are difficult to quickly scan. Sometimes files simply can’t be found and have to be recreated.

This content chaos all adds up to a lot of wasted time and resources…and frustration.

MAM software addresses this problem by providing teams with a single, searchable repository to store and organize all creative files — making asset retrieval a breeze.

How is media asset management software used?

While content management is important for all kinds of teams, MAM focuses on marketing assets and workflows. And the benefits of MAM are numerous — let’s explore some through common use cases.

Distributed marketing teams, one brand

It takes a village to bring a marketing strategy to life, and that village often includes numerous regional offices, remote workers, contracted agencies, and external partners. And all of these content creators and communicators need to be working towards a unified brand experience.

MAM software makes global brand management possible by providing a centralized platform to store and manage files, including brand guidelines and standards. So not only are dispersed team members working from the same playbook, but they are also using the same brand-approved assets — helping to ensure consistency across customer touchpoints.

Ease of use, powered by metadata

Marketing assets are central to workflows across an organization. For example, sales reps need current product materials for deal advancement and customer success managers use the same assets to support and educate existing customers. Their ability to work with agility depends on having these resources at their fingertips.

MAM software includes flexible metadata capabilities that power robust search tools, allowing users to locate an asset with just a few clicks — even in a repository of tens of thousands of files. Further, because MAM software offers easy-to-use versioning capabilities, users can be confident that assets are current. This efficiency accelerates workflows and fuels revenue growth.

Integrated systems and automated processes

A modern marketing technology (martech) stack includes numerous platforms to store, produce, and publish content, many of which include their own asset libraries.

By positioning a MAM system as the central source of truth for all content, teams can simplify content management and consolidate redundant tools. Powerful APIs and out-of-the-box connectors automate the flow of content from a MAM platform to other systems to ensure the same assets are used across digital destinations, without the need for manual updates across the content supply chain.

What are media asset management software options?

Organizations shopping for a MAM platform have an abundance of choices to consider. A simple search for “media asset management” on G2 — a large, online software marketplace — lists 82 products!

All of these platforms have big things in common. For example, most, if not all, are software as a service (SaaS) solutions in the cloud (versus on-premise software that is installed locally).

However, the specific features that each vendor offers can vary quite a bit. So the first step in any MAM software search is to clearly understand and outline the functionality needed for your unique workflows.

From there, you can really begin your research in earnest — or even start drafting a request for proposal (RFP).

The difference between MAM and DAM

In today’s enormous martech landscape media asset management overlaps with several other disciplines, including digital asset management (DAM).

While these two solution categories are similar (in name and practice), there are key differences.

DAM refers to the business process of storing and organizing all types of content across a company. This could mean files from the finance department, legal team, human resources, or other business units.

MAM, on the other hand, really focuses on assets that the marketing department requires, including large video and audio files.

So finding the solution that’s right for your team really starts with clarifying your functionality needs, including the types of files you want to store in your system and how you need to manage and distribute them.

Successful technology selection, with AVP

Is a MAM or DAM platform right for your organization? Further, which vendor is the best match for your marketing goals? While answering these questions can be hard, we can help.

AVP’s consultants have worked with hundreds of organizations to select the software partner that best fits their workflow and technology needs. If you’re dealing with content chaos, we’d love to hear from you.

Contact us to learn more about AVP Select — and how we can work together to achieve your content management goals, faster.

5 Warning Signs Your DAM Project is at Risk

12 September 2024

In the world of Digital Asset Management (DAM), recognizing early warning signs can mean the difference between success and failure. Chris Lacinak, founder and CEO of AVP, shares valuable insights from his extensive experience in the field. Here are the five key warning signs that indicate your DAM project may be at risk.

No Internal Champion

The absence of an internal champion can jeopardize your DAM project. This champion should possess the necessary expertise and experience to guide the initiative effectively. Pragmatically, it might sound like relying too heavily on external consultants or team members thinking they can manage without a dedicated point person. This reliance signals a potential failure in project management.

So, what does an effective internal champion look like? They need to:

- Have a solid understanding of the domain.

- Dedicate time solely to this project.

- Maintain the knowledge and context after external parties depart.

Having someone who can coordinate resources and make informed decisions is crucial for the sustainability and success of the project.

Insufficient Organizational Buy-In

Lack of organizational buy-in is another critical warning sign. If key stakeholders, especially leadership, do not understand the DAM initiative or fail to see its significance, the project is likely to struggle. This might manifest as leadership not being involved or departments feeling excluded from the process.

To foster buy-in, it’s vital to establish executive sponsorship early on. This sponsorship can come from various levels, including directors or C-level executives, who can advocate for the project and ensure it aligns with the organization’s strategic vision. Engaging with key stakeholders will help ensure they feel heard and included in the process, reducing potential pushback during implementation.

Inability to Articulate Pain Points

Another red flag is the inability to clearly articulate pain points. Statements like “we’re just a mess” or “we need a new DAM” indicate a lack of understanding of specific challenges. It’s essential to identify precise pain points to effectively address them.

Using the “Five Whys” technique can help drill down to the root of the problem. For instance, if a team is losing money, asking why repeatedly can reveal that the core issue might be difficulty in finding digital assets, leading to unnecessary recreations. This approach emphasizes that pain points are human problems, not just technological ones, and should be treated as such.

Unclear Definition of Success

Not knowing what success looks like or what the impact of solving the problem would be can lead to project derailment. If stakeholders cannot envision the outcome of a successful DAM implementation, it suggests a lack of direction and clarity.

To establish a strong business case, it’s crucial to articulate what success entails. Consider questions like:

- What will you be able to do that you couldn’t do before?

- What improvements will you see in workflows or team morale?

- How will this align with the organization’s strategic goals?

A well-defined vision of success helps secure leadership buy-in and provides a roadmap for measuring progress.

Skipping Critical Steps in the Process

Finally, wanting to skip critical steps or prematurely determining solutions can be detrimental. Statements like “we did discovery a couple of years ago” or “we just need a new DAM” indicate a lack of thoroughness in the planning process.

Discovery is essential for gathering updated information and engaging stakeholders. If stakeholders feel involved in the process, they are more likely to support the initiative and its outcomes. Rushing through this phase can lead to poor decisions and wasted resources, ultimately putting the project’s success at risk.

Conclusion

Identifying these five warning signs early on can help mitigate risks associated with your DAM project. Establishing an internal champion, ensuring organizational buy-in, articulating pain points, defining success, and taking the time to conduct thorough discovery are all critical steps toward a successful DAM implementation. By addressing these areas proactively, you can set your project up for success and avoid common pitfalls.

If you found this information helpful or have further questions, feel free to reach out to Chris Lacinak at AVP for more insights into managing your DAM projects effectively.

Transcript

Chris Lacinak: 00:00

Hey, y’all, Chris Lacinak here.

If you’re a listener on the podcast, you know me as the host of the DAM Right Podcast.

You may not know me as the Founder and CEO of digital asset management consulting firm, AVP.I founded the company back in: 2006

And I have learned what the early indicators are that are likely to make a project successful or a failure.

And I’m gonna share with you today five warning signs that your project is at risk.

So let’s jump in.

Number one, there is no internal champion to see things through, or there’s an over-reliance on external parties.

Now, what’s that sound like pragmatically?

That sounds like, “that’s why we’re hiring a consultant”, or “between the three of us, I think we should be able to stay on top of things.”

You might think it’s funny that myself as a consultant is telling you that you should not have an over-reliance on external parties, but the truth of the matter is, is that if you are over-reliant on us, and you are dependent on us, we have failed to do our job.Chris Lacinak: 01:06

That is a sign of failure.

But let’s talk about the champion.

What’s the champion look like?

Well, first and foremost, it’s someone who has the right expertise and experience.

We wanna set this person up for success.

They need to have an understanding of the domain.

They don’t have to be the most expert person, but they need to understand, they need to be conversant, they need to understand the players, the parts, how things work.

They need to be knowledgeable enough that they’re able to do the job.

Second, they need to have the time.

This can’t be, you know, one of ten things that this person is doing, part of their job.

It needs to be dedicated.

And it can’t be something that’s shared across three, four, five people.

That’s not gonna work either.

Things will slip through the cracks.

Now, why is this important?

Well, it’s important because it mitigates the reliance on external parties, as I’ve already said.

But what’s the other significance?

The other significance is that once the consultant leaves, or once the main project team is done doing what they’re doing, whether that’s an internal project team or external project team, this person is gonna be the point person that is going to maintain the knowledge, the history, the context of the project.Chris Lacinak: 02:14

They’re gonna have an understanding of what the strategy, what the roadmap is, what the plan is, and they’re gonna help execute that.

They’re gonna be the point person for coordinating the various resources, the people.

And, you know, it’s gonna depend what this position looks like as to what authority they have, what budget control they have, things like that, about exactly what it looks like.

But more or less, this person is either gonna be, you know, the main point of recommendations and influence, or they might even be the budget holder and actually be making the calls and decisions.

But one way or another, you need somebody that is gonna see this through, that’s internal to your organization in order for it to be sustainable and for it to succeed.

Number two, not enough organizational buy-in or poor socialization.

What’s that sound like in practice?

Well, it might sound like “leadership doesn’t understand, they just don’t get it.”

Or “there’s issues with that department that we don’t need to go into here, but we don’t need to include them.

They’ll have to fall into place once we do this.”

Or “we haven’t talked with folks about this yet, but we know it’s a problem that needs to be fixed.

It’s obvious.”Chris Lacinak: 03:14

Those are all signs that there’s poor socialization and that you haven’t gotten the appropriate buy-in from the organizational key stakeholders.

Now, who are the key stakeholders?

Well, let’s start with executive sponsorship.

It’s critically important that there’s an executive sponsor.

Now, executive can mean a number of things.

It could be director level, it could be C-level.

Essentially, it’s someone who is making decisions, is a key part of fulfilling strategy for the organization, the department, the business unit, has budget and is making budget calls.

So why is this important and how do you respond to this?

Well, it’s important because executive sponsorship is looking out for the vision, the strategy, the mission, and the budget of the organizational unit.Chris Lacinak: 03:59

You can’t be sneaky and successfully slip a DAM into an organization, right?

There’s no such thing as a contraband dam.

It’s not like that bag of chips you sneak into the grocery cart when your significant other is looking the other way.

It’s an operation, it’s a program.

It requires executive sponsorship.

It requires budget.

It requires a tie-in into the strategy, the vision, and the mission.

It’s not a bag of chips.

It’s all that and a bag of chips.

Who are the other key stakeholders?

Well, your key stakeholders are gonna be the other people that are either contributors, users, or supporters of the DAM in some way.

‘Cause it is an operation.

A dam has implications to workflows, to policies, to behaviors.

It touches so many different parts of the organization.

So it’s critically important that your key stakeholders are included as early on in the process so that they feel heard, they feel included, they feel represented.

And when it’s time to roll out that DAM, you don’t have people going and looking backwards, right?Chris Lacinak: 04:57

Everybody has an understanding of where you are, why you’ve arrived there, and how you’re moving forward.

And even if they don’t agree, they understand and they’re on board.

And you want concerns and objections.

You want those, as I said, not at the point at which you’re trying to do the thing, but you want it early on.

You wanna be able to respond to those.

You wanna be able to address them.

You hope they come out as early as possible so that you can build allies and trust as early on in the process as possible.

Now, do not confuse this with getting consensus and doing everything by consensus.

That is not what I mean.

And in fact, that could stand on its own as a major warning of potential failure here.

So doing everything by consensus is a huge downfall.

Do not go that route.

You want a robust, diligent system and a process for planning and executing the project that uses and addresses feedback of people along the way, but not one that requires everybody to agree on something.Chris Lacinak: 06:01

And not one where everybody’s wants and wishes are treated equally, right?

That’s just not how organizations work.

If you do that, you’re gonna end up with a system that makes nobody happy ’cause you’re not doing anything particularly well.

So it’s a setup for failure.

So do not do that.

And you might think, well, if I don’t give people what they want, if I tell people no, if we say their issue is a priority three instead of a priority one, they’re gonna object to the system or the program.

And that’s not true.

Actually, what people want, they wanna feel heard, right?

They wanna be able to raise their concerns, their objections, their wishes.

Then they wanna know that you hear them.

They want to understand why whoever’s making the decisions are making the decisions the way they are.

So if their issue or their wish or their request is number three instead of number one, people can live with that.Chris Lacinak: 07:02

If they understand why you’ve made that decision, you’ve addressed it, it’s transparent, and it serves the greater mission, vision, or purpose of what you’re trying to do.

So that is critical.

You need to lay out that mission, vision, purpose early on.

And again, if you look at our DAM operational model, that is at the center of the operational model.

Once you have people on board with that, then you can start to get people to organize around that.

And even if they don’t get everything they want, they’re willing to be on board and be a productive member of obtaining that greater goal.

Number three, unable to clearly articulate the pain points.

So what’s that sound like in practice?

Well, it sounds like something like, “we’re just a mess.

My friend works at such and such organization, they have their act together, we need to be like them.”

Or “we definitely just need a new DAM.

Jerry was in charge of getting the one we have now and nobody likes Jerry.”Chris Lacinak: 08:01

So that’s not often a good place to start.

You know, well, and maybe you do start there.

It’s not a good place to end.

You don’t act off of that point.

That begs more questions.

And here’s what I’ll say, you know, and I’ve been, I’m a buyer of services where I’m not an expert.

So there are things that I know I don’t know.

And I might have trouble talking to, you know, a service provider for me, not understanding what the landscape of service offerings are or exactly what I need, right?

You don’t need to know what you need or what the solution is.

It’s okay that you don’t know what you don’t know.

That’s not the problem.

That’s something where you can get, you know, the service provider that I’m talking to, or if you’re talking to AVP, we can guide you on that.

We will get enough context and understanding to be able to guide you on that.Chris Lacinak: 09:02

What we need to know is what your pain points are.

So imagine going to the doctor, you have a hurt knee and maybe that hurt knee has you worried.

So your stomach’s upset with worry and you’re feeling down in the dumps because you’re not feeling well.

You need to be able to articulate the relevant pain points to the doctor, right?

You can’t just go in and say, “Oh, I feel awful.”

“Well, what’s wrong?”

“Everything.”

No, that’s not gonna help anybody.

You need to be able to say at least my knee is hurting.

That’s the main problem.

If there’s information and context on what caused that, that’s great and useful.

You know, “I had a fall.”

“I twisted it when I was on the trail”, whatever the case may be.

That might be helpful information, but you don’t need to know why your knee hurts and you don’t need to know what the solution is.

You just need to be able to point the doctor in the right direction of where the pain is.

Similarly with DAMS, right?

So let me give you a tip for identifying pain points.

I talked about, I gave those examples of what it sounds like up front.

And I said, you know, that might be an okay place to start.

I mean, it might be.Chris Lacinak: 10:01

Sometimes you’re just frustrated, you’re overwhelmed, right?

And that’s the thing that comes out.

But that’s not the place you end.

So there’s something called the five whys.

It comes out of a root cause analysis that I think can be really useful here.

And I’ll give you as a tool to use for kind of drilling down on what the pain points are.

So let’s give an example.

Let’s state a problem.

And then you ask why five times to get down to the core of the problem.

So let’s say we start at, “we’re just a mess.”

Well, why?

“Well, we’re losing money.”

Why is that?

“Because we keep missing deadlines and going over budget on production expenses.”

Well, why is that?

“Well, because people continuously have to recreate assets that we’ve already created in the past, and that just takes more time and more money.”

Well, why is that?

“Because people can’t find what they’re looking for.

They have to recreate it.

Or maybe it’s lost and we have to recreate it.”

Well, why?

“Well, because when they search for things using the terms that are meaningful to them, they don’t get the right results.Chris Lacinak: 11:00

They don’t get the things they are looking for.

And it takes too much time and it’s too hard.”

Now that is extremely useful, right?

That’s where we get down to the pain points.

People can’t find what they’re looking for.

That gives us something to work with.

And remember here too, you put humans first.

Pain points are not technology problems, they’re human problems.

And we’re aiming to solve human problems.

Now, technology has a role to play in solving these problems, but technology problems are not what we’re aiming to solve.

The problem is not that you don’t have a DAM.

The problem is that the digital assets can’t be found easily.

Digital assets are being lost and recreated.

Licensed content is being misused.

Brand guidelines are being violated.

All of these things cause pain to people in the way of time, money, frustration, excellence, et cetera.

So one solution to this may be a DAM technology, but there’s more to it than just that.

And again, I’m gonna point you to the DAM Op model.

Number four, you’re unable to understand what success looks like or what the impact of solving the problem would be.Chris Lacinak: 12:01

And that sounds like, (crickets chirping) crickets.

I always like to ask, if you could solve all of these pain points and problems, and if this project is a total success, imagine, what does it look like?

What are you able to do that you couldn’t do before?

What do you have that you didn’t have before?

And this ties back to pain points ultimately, and you put them together to make what’s called a business case.

And while it’s always a great idea for a business case to get down to dollars, it doesn’t have to.

So don’t be distracted by the money.

Let’s go for the money, that’s important, and I’ll talk about why.

But don’t be distracted by that.

Let’s talk about the other things too, ’cause there are qualitative factors that are meaningful and important as well.

For instance, you might say, “if we could solve the search problem, we’d be able to come in on or under deadline and budget.

The team would have a much better work experience, people would feel happier, less frustrated.

The CEO or executive director would be ecstatic because we’d be able to support three of their five key strategies over the next year.

We’d be able to reduce storage costs by 200%.Chris Lacinak: 13:01

We could cut the legal budget for license fee violations by 90%”, right?

And I’m gonna link to a business case post and slide deck template that we have for you to help you there.

And I’m gonna encourage you to go and check that out.

But the point here is that you need to be able to articulate what success looks like.

And tied into the vision and strategies of the organization and leadership, that puts so much wind in the sail of your DAM project.

Less pain is one thing, but more joy is even better.

If you don’t have a strong business case and you can’t speak to what success looks like or what the impact will be, I’m gonna say it’s unlikely that you truly have the buy-in of leadership.

Or that there’s even a sustainable path forward that is at least clear today.

Why?

Well, because leadership, whether it’s at a Fortune 500 or a nonprofit or higher ed institution, prioritizes where they spend their resources based on how well it supports their vision, strategies and mission.Chris Lacinak: 14:04

If you can’t convince them and demonstrate how your DAM project will do that, then you’re not going to get anything more than play money.

What do I mean by play money?

It’s something that keeps you busy and out of their hair while they go about realizing their vision, strategy and mission.

It’s not a sustaining revenue source.

It’s not a sustaining funding source, I should say, in order to support a DAM project and program.

Also, if you don’t know what you’re aiming for, how can you measure, track, report, prove, and improve?

In order to keep the attention of leadership, you need to be able to consistently demonstrate the value of the DAM program.

And aside from leadership, it also creates direction orientation for the organization.

Number five, wanting to skip critical steps or predetermining that you need something you don’t.

What’s this sound like in practice?

It might sound like, “We did discovery a couple of years ago.

We’ll use that so we can do this faster or cheaper.”

Or, “We know we just need a new DAM.

Let’s just focus on that.”Chris Lacinak: 15:03

Or it might sound like, “We’re just a mess.

My friend works at such and such organization and they have Acme DAM and it works great.

And nobody likes our DAM vendor anyway.

We just need a new DAM.”

Well, let’s start with the discovery part.

So the reality is that discovery serves multiple purposes.

One purpose is information, right?

And in six months or twelve months or two years, things change and can change dramatically.

So for just informational purposes, you’re setting the foundation up here for your strategy, your plan, your implementation, whatever it is, you don’t wanna take a risk on getting that wrong.

Make sure that your information is up to date, it’s accurate, it’s robust, right?

I wouldn’t use information from six months ago or two years ago as a stand-in for today for that reason.

But discovery serves other purposes.

Discovery gets stakeholders, key stakeholders specifically, sitting down at the table and engaging.Chris Lacinak: 16:07

That’s critically important for change management, for buy-in.

Earlier, we talked about getting those objections and concerns out on the table as early as possible.

It does that.

It gets people talking, people feel included, they feel part of the process.

It greatly increases from a human and organizational perspective, the success probability.

So you wanna get people down and engaging in this process early on.

The other funny thing about this is that someone is coming, when they’ve predetermined, we just need a new DAM.

Someone’s coming to an expert that they have sought out, seeking their expertise and their experience.

And they are, in that regard, they have acknowledged that they don’t have the appropriate expertise and experience.

On the other hand, they are sure that they know best, better than the person’s expertise and experience that they’ve sought out.Chris Lacinak: 17:02

So let’s start with, “we’re just a mess.

My friend works at such and such organization and they have Acme DAM.”

They might go on to say, “we know we need Acme DAM and we just need you to convince procurement that we need Acme DAM and get them to get it for us.”

This is like going to your doctor with a hurt knee and saying, “my friend got a knee replacement and it did them wonders.

I know I just need a knee replacement and I need you to convince the insurance company to pay for it.”

Now, it’s possible you need a knee replacement, just like it’s possible that this organization needs a new DAM.

And it’s within the realm of possibility that this organization would benefit from Acme DAM and you would benefit from a new knee.

But if that doctor says, “okay, let’s look at the surgery schedule, how’s noon today work?”

You should run.

Well, maybe don’t run.

You do have a hurt knee after all, walk briskly out of there and don’t go back.

Similarly, if a consultant says, “okay, let’s get to work on getting you that Acme DAM” after that conversation, you should run, which is okay in this scenario because you don’t have a hurt knee as far as I know.Chris Lacinak: 18:03

The real deal is that there are lots of reasons that DAM operations and programs don’t work.

That experienced doctor is gonna look at your gait, at how you hold your body, ask questions about your activities, look at whether it’s a bone or a tendon issue, et cetera.

They’re gonna look systematically and holistically before making a judgment call in the best course of action.

And that’s exactly what you or your DAM consultant should do in this scenario in order to stand the best chance of getting to success in the fastest and most cost-effective manner.

Because the disaster scenario is that you get the new knee or you get the new DAM and not only does it not make things better, but it makes them worse.

In the knee situation, you’ve only hurt yourself.

It’s still unfortunate, but you’ve only hurt yourself.

In the DAM scenario, you’ve likely wasted hundreds of thousands of dollars.

You stand to lose more.

You’ve lost trust.

You’ve hurt morale.

You’ve possibly put your job at risk.

So there’s a lot to lose.

And I’m gonna link to a blog that we wrote about the cost of getting it wrong, just so that you can understand a little bit better why you don’t wanna go that route.Chris Lacinak: 19:02

So those are the five warning signs that your DAM project is at risk.

I hope that you have found this extremely helpful.

Please email me at [email protected].

Leave comments, like, and subscribe.

Let me know how you liked it.

And let me know if you’d like to see more content like this or hear more content like this.

Thanks for joining me today.

Look forward to seeing you at the next DAM Right Podcast.

Exploring the Future of Object Storage with Wasabi AiR

8 August 2024

In today’s data-driven world, object storage is revolutionizing how we manage digital assets. Wasabi AiR, an innovative platform, uses AI-driven metadata to enhance this storage method, making it more efficient and accessible. This blog explores how Wasabi AiR is reshaping data management, the benefits it offers, and what the future holds for AI in this field.

How Wasabi AiR Transforms Object Storage

Wasabi AiR integrates AI directly into storage systems, automatically generating rich, searchable metadata. This feature allows users to find, manage, and utilize their data more effectively. By enhancing storage with AI, Wasabi AiR helps organizations streamline data retrieval, boosting overall productivity and efficiency.

The Evolution of Metadata in Object Storage

While AI-generated metadata has existed for nearly a decade, its adoption in data storage has been slow. Wasabi AiR simplifies this integration, allowing organizations to leverage automation without complexity.

Aaron Edell’s Vision for AI in Storage

Aaron Edell, Senior Vice President of AI at Wasabi, leads the Wasabi AiR initiative. His vision is to make AI a seamless part of data management, enabling organizations to generate metadata effortlessly and manage digital assets more efficiently.

Advanced Technology in Wasabi AiR

Wasabi AiR uses advanced AI models, including speech recognition, object detection, and OCR, to create detailed metadata. This capability enhances the storage system by making data more searchable and accessible. One standout feature is timeline-based metadata, enabling users to locate specific moments within videos or audio files stored in their systems.

Use Cases: How Wasabi AiR Benefits Different Sectors

Wasabi AiR has numerous applications across industries, improving data handling in:

- Media and Entertainment: It helps create highlight reels quickly, as seen with Liverpool Football Club’s use of Wasabi AiR to boost fan engagement.

- Legal Firms: Law firms save time by managing extensive video and audio records efficiently.

- Education and Research: Institutions make their archived content more accessible through AI-driven metadata.

Cost Efficiency of AI-Powered Data Storage

Wasabi AiR offers a cost-effective solution, charging $6.99 per terabyte monthly. This straightforward pricing makes it easier for organizations to predict costs while benefiting from AI-enhanced solutions.

Activating Wasabi AiR

Setting up Wasabi AiR is simple. Users connect it to their existing system, and the platform begins generating metadata immediately, enhancing value and usability without requiring complex configurations.

The Future with AI

As data continues to grow, efficient management is increasingly important. Wasabi AiR is set to play a key role by enhancing searchability and usability through AI-driven solutions.

Integration and Interoperability

Wasabi AiR supports integration with other data management systems, enhancing workflows. Its APIs allow seamless metadata export to Digital Asset Management (DAM) or Media Asset Management (MAM) systems, making data handling more efficient.

Ethical AI Considerations

Ethical considerations are crucial when implementing AI in data management. Wasabi AiR ensures data security and transparency, building trust and ensuring responsible AI use.

Conclusion: Elevating Data Management with AI

Wasabi AiR is a game-changer, enhancing how we manage, search, and utilize data. By combining AI with innovative technology, organizations can significantly improve efficiency, accessibility, and data management. As digital data management continues to evolve, Wasabi AiR positions itself as a leader, offering a future where data isn’t just stored—it’s actively leveraged for success.

Transcript

Chris Lacinak: 00:00

The practice of using AI to generate metadata has been around for almost a decade now.

Even with pretty sophisticated and high-quality platforms and tools, it’s still fair to say that the hype has far outpaced the adoption and utilization.

My guest today is Aaron Edell from Wasabi.

Aaron is one of the folks that is working on making AI so easy to use that we collectively glide over the hurdle of putting effort into using AI and find ourselves happily reaping the rewards without ever having had to do much work to get there.

It’s interesting to note the commonalities and approach with both Aaron and the AMP Project

folks who I spoke with a couple of episodes ago.

Both looked at this problem and aimed to tackle it by bringing together a suite of AI tools

into a platform that orchestrates their capabilities to produce a result that is greater than the

sum of their individual parts.

Aaron is currently the SVP of AI at Wasabi.

Prior to this, he was the CEO of GreyMeta, served as the Global Head of Business and

GTM at Amazon Web Services, and was involved in multiple AI and ML businesses in founding

and leadership roles.

Aaron’s current focus is on the Wasabi AiR platform, which they announced just before

I interviewed him.

I think you’ll find his insights to be interesting and thought-provoking.

He’s clearly someone who has thought about this topic a lot, and he has a lot to share

that listeners will find valuable and fun.

Before we dive in, I would really appreciate it if you would take two seconds to follow,

rate, or subscribe on your platform of choice.

And remember, DAM Right, because it’s too important to get wrong.

Aaron Edell, welcome to the DAM Right podcast.

Great to have you here.

Aaron Edell: 01:38

It’s an honor.

Chris Lacinak: 01:40

Thank you for having me. I’m very excited to talk to you today for a number of reasons.

One, you’ve recently announced a really exciting development at Wasabi. Can’t wait to talk about that.

But also, our career paths have paralleled and intersected in kind of strange ways over

the past couple decades.

We both have a career start and an intersection around a guy by the name of Jim Lindner, who

was the founder of Vidipax, a place that I worked for a number of years before I started

AVP, and who was also the founder of Samba, where you kind of, I won’t say you started

there, you had a career before that, but that’s where our intersection started.

But I’d love for you to tell me a bit about your history and your path that brought you

to where you are today.

Aaron Edell: 02:34

Yeah, definitely.

The other funny thing about Jim is that he is a fellow tall person. So folks who are listening to this can’t tell, but I’m six foot six, and I believe Jim is

also six six or maybe six seven.

So when you get to that height, there’s a little Wi-Fi that goes on between people of

similar height that you just make a little connection.

You kind of look at each other and go, “I know your pain.

I know your back hurts.”

So my whole life growing up, ever since really I was five years old, I loved video, recording,

shooting movies, filming things.

I eventually went to college for it.

I did it a lot in high school.

And this is back in the early 90s when video editing was hard.

And the kid in high school who knew how to do it and had the Mac who could do it was

kind of the only person able to actually create content.

So I was rarefied, I guess, in that sense.

So I would go to film festivals and all sorts, and it was just great time.

And I was never very good at it.

I just really loved it.

And when you love something, especially when you’re young, you learn all of the things

you need to know to accomplish that.

So I learned a lot about digital video just because I had to figure out how to get my

stupid Mac to record and transcode.

And then I got introduced to nonlinear editing very early on and learning that.

So when I went to college, I went there for film and video, really.

That was what I thought I wanted to be when I grew up was a filmmaker.

My father was talent for KGO television and ABC News for a long time.

So I had some familial– and my mother was the executive producer of his radio show.

So I had a lot of familial, sort of, media and entertainment world around and was very

supported in that way, I suppose.

By the time I got– so I went to college, and I loved my college.

Hampshire College is a fantastic institution.

It has no tests, no grades.

It has a– you design your own education, which is not something I was prepared for,

by the way, when I went there.

I’m so thrilled I went there because all of my entrepreneurial success is because of what

I learned there.

But at the time, I had no appreciation for that.

And I just thought, well, this is strange.

I’m here for film and video, and they’re like, here’s a camera.

Here’s a recording button.

And I thought, mm, this is an expensive private college in Massachusetts and probably need

to make it a little bit harder.

So my father is a physician, so I thought pre-med.

And I did it.

I went full on pre-med.

I was going to be a doctor.

I was going to apply to medical school.

But I was also working on documentaries and producing stuff and acting in other people’s

films and things like that.

So I still– that love, that passion never went away.

I was just kind of being creative about how to do it.

And my thesis project ended up being a documentary about a medical subject, which was kind of

perfect.

Because at the end of the day, my father, he’s a physician, but he’s actually a medical reporter.

And that’s a whole separate field that fascinated me.

So when I graduated, I was like, OK.

I went and actually got a job producing and editing a show for PBS, which was super cool

in New York City.

And that was around: 2000

I was doing it for a couple of years.

And we were– it was a PBS show, so we were very reliant on donations and whatnot.

And: 2008

It dried up.

We ran out of money.

And I was looking for a job.

And I worked on a couple of movies that were being shot in the city.

And I found this job at this weird company called SAMMA Systems on 10th Avenue and 33rd

Street or something that was Jim Lindner’s company.

That came to learn later.

But they were making these robotic systems that would migrate videocassette tapes to

a digital format.

So think of a bunch of tape decks on top of each other with a gripper going up and down

and pulling videotapes out of a library, putting them in, waiting for them to be digitized,

taking them out, cleaning them– not in that order, but essentially that way.

And I was just fascinated.

I mean, it was so cool.

Building robots.

Chris Lacinak: 07:02

Yeah.

Aaron Edell: 07:03

You know, video.

It was everything I loved kind of in one. And the rest is just really history from there.

Chris Lacinak: 07:09

Yeah.

So we have another intersection that I didn’t know about, which was Hampshire College, although I was denied by Hampshire College.

So you definitely one-upped me on that.

Which I taught at NYU in the MIAP program, and Bill Brand also taught there, also taught

at Hampshire College.

And I told him that I was denied by Hampshire College.

And he said, I didn’t know they denied people from Hampshire College.

Aaron Edell: 07:30

Oh, that makes it worse.

Chris Lacinak: 07:32

Anyway, all things happen for a reason.

It was all good. But that’s very cool.

That is a great school.

And what a fascinating history there.

So it’s not– I mean, I still think there’s– let’s connect the dots between working for

a company that was doing mass digitization of audiovisual and where you are today at

Wasabi.

Like, that is not necessarily easy to fill in that gap.

So tell us a little bit about how that happened.

Aaron Edell: 08:00

Yes.

Well, as my father likes to say, you know, life is simply a river. You just jump in and kind of flow down and you end up where you end up.

I don’t think I could have engineered or controlled this.

p– you know, SAMMA, this was: 2008

If I could jump back, you know, and say to myself back then, this is where you’re going

to end up, I would just been like, how?

How do you do that?

How is that possible?

So this is what happened.

I mean, I– you know, SAMMA was very quickly acquired by a company called Front Porch Digital

in: 2000

Very close to: 2009

And Front Porch Digital, you know, created these products that were– the core product

was called DIVA Archive, which still exists today, although it’s owned by Telestream.

But essentially, it is– you know, you’ve got your LTO tape robot and you’ve got your

disk storage and you have– you’re a broadcaster.

And you need some system to keep track of where all of these files and digital assets

live and exist.

And you’ve got to build in rules.

Like, take it off spinning disk if it’s old.

Make sure that there’s always two or three LTO tape backups.

You know, transcode a copy for my man over here.

Automation wants some video clip for the news segment.

You know, pull it off tape and put it here.

All of that kind of stuff was the DIVA Archive software.

And I’m oversimplifying.

But through that process, you know, I was– I joined as the– I was kind of bottom of

the rung, like, support engineer.

And I had delivered some SAMMA systems, you know, installed some and did a little product

managing just because we were– you know, we needed it.

We were only eight people.

And I was probably the most knowledgeable of the system other than one or two people

at the time.

And so by the time I got to Front Porch Digital, you know, I was doing demos and I was– I

was architecting solutions for customers.

So I was promoted to a solutions architect.

And that’s kind of where I learned, you know, business, just like generic business stuff,

emails, quotes.

I learned about the tech industry and media and entertainment industry in particular and

how, you know, how sales works in those industries and how it doesn’t work sometimes.

And all of the products that are– that are involved.

So I was kind of, you know, getting a real good crash course of just how media and entertainment

works from a tech perspective and how to be a vendor in the space.

I did a brief stint at New Line.

For those of you who don’t know New Line, I don’t think it exists anymore, but it was

a company based in Long Island that kind of pioneered some of the like set-top box digital

video fast channel stuff.

And then– but I was more or less at Front Porch for about seven years.

And then Front Porch was acquired by Oracle.

And working at Oracle was a very different experience.

You know, they are a very, very large company and they have a lot of products.

And I don’t know, I just– it just didn’t feel like I could do my scrappy startup thing,

which I had kind of spent the last 10 years honing.

So that is– so, you know, that is kind of at the point where I– a sales guy that I

had worked with at Front Porch named Tim Stockhaus went off to California to start this company

called GrayMeta based on this idea that we were all kind of floating around, which is,

man, metadata is a real problem in the industry right now, especially as it relates to archives

and finding things.

So GrayMeta was founded on that idea.

When I joined there, I was the first or second employee.

So it was– we were building it from scratch.

And I mean building everything, not just the product or the technology, but the sales motions

that go to market.

And that’s where I learned all that stuff.

I quit GrayMeta about two years in to go start my own startup because I just wanted to do

it.

I wanted to be a founder.

I wanted to know what that was like.

And I, at that point, had learned a lot about machine learning and how it applies to the

media and entertainment industry, specifically around things like transcription and AI tags.

And a couple of my coworkers at GrayMeta had this really great idea that let’s build our

own machine learning models and make them Docker containers that have their own API

built in and their own interface and just make them run anywhere, run on-prem, run in

the cloud, wherever you want.

Because it solved a lot of the problems at the time.

So we jumped ship.

We built the company.

It exploded.

I was the CEO.

My founders were the technical leaders.

And between the three of us, man, we were doing everything– sales, marketing, building,

tech support, all of it.

And gosh, what a learning experience.

Also as a founder and CEO, you’re raising money.

You’ve got to figure out how the IRS works.

You need to figure out how to incorporate stuff.

So a whole other learning experience for me.

a company called Veritone in: 2019

Changed our lives.

I mean, we went through an acquisition.

We walked away with a lot of money.

And it was a whole new world.

Things open up, I guess, when that happens to you in business.

And I actually got recruited to join AWS.

And the funny thing is that it had nothing to do with media and entertainment or AI at

all.

AWS said, hey, you have a lot of experience taking situations where there’s a lot of data

and simplifying it for people or building products to simplify it for people and make

it more consumable and understandable.

AWS has that problem with their cost and usage data.

Chris Lacinak: 13:47

Oh, interesting.

Aaron Edell: 13:49

Yeah. And you get a, especially if you use a lot of the cloud and you’re a big company, you

get a bill. It’s not really a bill.

You get like this data dump that’s not human readable.

It’s billions of lines long, has hundreds of columns.

You can’t even open it in Excel.

It’s like, how do I use this?

So AWS was like, go figure this out, man.

So I mean, gosh, it was such a great experience.

We built a whole business based on this idea.

We built a product.

We built a go to market function.

We changed how AWS and actually I think how the world consumes cloud spending.

I think we had that big of an impact, not to toot our own horn, but it was for me, for

my career and my learning as a human, wow.

Like seeing how you can impact the whole world.

Chris Lacinak: 14:39

Yeah.

Well, as a consumer of AWS web services, I’ll say thanks because the billing definitely improved dramatically over the past several years.

So I know exactly what you mean.

And I see the manifestation of your work there.

I didn’t realize though that that’s what you’re doing at AWS.

I did always have in my mind that it was on the AI front.

So that’s really interesting that you kind of left that.

So in some ways, your role now is kind of a combination of the two in the sense that

Wasabi is a competitor to AWS, but you are very much in the AI space.

So tell us about what you’re doing at Wasabi now.

Aaron Edell: 15:17

Yeah, absolutely.

Well, you know, it was your point is really spot on because one of the biggest problems, I think for customers of the cloud is that, and I learned this thoroughly, is that it’s

not forecastable and it’s really hard to actually figure out what you’re spending money on.

And it’s also can be expensive if you do it wrong.

There really is a right way to do cloud in a wrong way.

And it’s not always obvious how to navigate that.

So when I first came up, so, you know, the board of GrayMeta called me while I was AWS,

you know, kind of chugging along and said, “Hey, Aaron, why don’t you come and be CEO?”

And I thought, you know what, that’s scary.

But it’s also like, it’s perfect because the Graymeta story, I feel like we never got to

finish telling it.

I left, you know, before we got to finish telling it.

And so I came back and I said, “Guys, I’ve now had the experience of creating our own

machine learning models and running a machine learning company, like one that actually makes

AI and solves problems.

Let’s do that.”

So that’s when I met Wasabi, was very shortly after I came back.

And you are totally right, because when I met Wasabi, it was like a door opening with

all this, you know, heavenly light coming through in terms of cloud FinOps.

Because Wasabi is, you know, cloud object storage, just like S3 or Microsoft Blob, that

is just $7.99 per terabyte and, sorry, $6.99 per terabyte and just totally predictable.

Like, you don’t get charged for API fees, you don’t get charged for egress, which is

where the kind of complexity comes in for other hyperscalers in terms of cost optimization

and understanding your cloud use and cloud spend.

That’s all the unpredictable stuff.

That’s what makes it not forecastable.

So the fact that, you know, Wasabi has just like a flat per terabyte per month pricing

and there’s just nothing else.

It’s just elegant and simple and beautiful and very compelling for the kind of experience

I had in the, and we call it the FinOps space or cloud FinOps space, where for three and

a half years, all I heard were problems about that this solved, right?

So it just pinged in my brain immediately.

The connection with AI, you know, goes back even further in the sense that I had always

advocated for, I always believed fundamentally that the metadata for an object and the object

itself should be as closely held together as possible.

Because when you start separating them and they’re serviced by different vendors or whatever,

that’s where the problems can seep in.

And one of the best analogies for this that I can think of is, you know, our Wasabi CEO,

Dave Friend, I love how he put it because he always refers to, you know, a library needs

a card catalog, right?

You go into the library and the card catalog is in the library.

You don’t go across the street to a different building for the card catalog, right?

It’s the same concept.

I mean, it’s obviously, you know, the physical world versus the virtual computer world, but

similar concept in the sense that, you know, the metadata that describes your content,

it should be as close to the content as possible because if it’s not, you know, you are at

risk of losing data at the end of the day.

I mean, I’ve talked to so many customers that have these massive libraries, sometimes they’re

LTO libraries, sometimes there are other kinds of libraries where they’ve lost the database,

right?

And, you know, in LTO, like you need a database.

You need to know what objects are written on what tape.

It’s gone.

I mean, what do you do, right?

You’re in such a bad, it’s such a bad spot to be in.

So hopefully we’re addressing that.

Chris Lacinak: 19:18

Yeah.

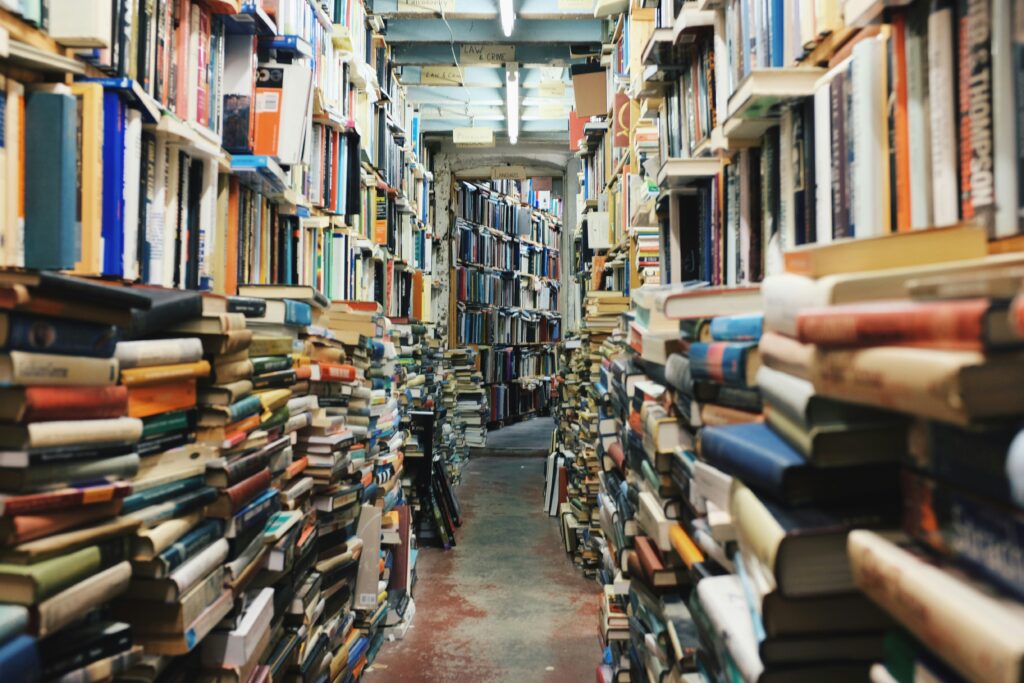

So that’s, I remember reading something on your website or maybe a spec sheet or something for air, which said object storage without a catalog is like the internet without a search

engine or something.

So, and to take that, to tie that to your other analogy, it’s like a library without

a card catalog, right?

You walk in, you just have to start pulling books off the shelves and seeing what you

find.

Although there, we have a lot of text-based information.

When you pull a tape out of a box or a file off of a server, there’s a lot more research

to do than there is maybe even with a book.

So yeah.

Aaron Edell: 19:55

Yes.

Chris Lacinak: 19:56

So tell me, what does AiR stand for?

It’s a capital A lowercase i capital R. Tell us about that. What’s that mean?

Aaron Edell: 20:05

So I believe it stands for AI recognition.

Chris Lacinak: 20:08

Okay.

Aaron Edell: 20:09

And so the idea is that, so the product wasabi AiR is this new product and it’s, you know,

the kind of combination of the acquits. So I guess we skipped the important part, which is that wasabi acquired the Curio product

and some of the people, including myself came over and the Curio product really was this

platform.

We called it a data platform, if you will, that when you pointed at video files and libraries

and archives, it literally, it would do the job of opening up each file, like you just

said and watch essentially watching it, you know, logging, you know, taking it, making

a transcript of all the speech, looking at OCR information.

So, you know, recognizing text on screen, recording that down, pull, you know, pulling

down faces, object recognition, basically creating a kind of rich metadata entry for

each file.

So this is where I think the, the, the kind of marriage between that technology and Wasabi

comes in because you’re, we now have a way of essentially with wasabi AiR it’s, you know,

it’s your standard object storage bucket.

Now you can just say anything that’s in that bucket.

I want it, I want a metadata index for that.

We’ll just do automatically with machine learning and you have access to that and you can search

and you can see the metadata along a timeline, which is really kind of turning out to be

quite unique.

I’m surprised that I don’t see that at a lot of other places in specifically seeing the

metadata along the timeline.

And that’s important because the whole point, it’s not just search, it’s not just, I want

to find assets where there’s a guy wearing a green shirt with the Wasabi logo.

I want to know where in that asset those things appear because I’m an editor and I need to

jump to those moments quickly.

Chris Lacinak: 21:54

Right, right, right.

Aaron Edell: 21:56

So that, that’s, that’s what we’re doing at, at, at wasabi with wasabi AIR.

And that’s, that’s why AiR stands for recognition, AI recognition, because you know, we’re essentially running AI against and recognizing objects, logos, faces, people, sounds for all your

assets.

So I want to dive into that, but before we do that, on the acquisition front, did Wasabi acquire

a product from GrayMeta or did wasabi acquire GrayMeta?

Wasabi acquired the product, the Curio product.

So GrayMeta still exists.

In fact, it’s really quite, is thriving with the Iris product and the SAMMA product, which

we talked about SAMMA.

That was the other piece I skipped over that too.

When I, when they called me and said, come be CEO of GrayMeta, it really made sense because

SAMMA was part of that story.

And that, that was like a connection to my first job in tech, which was wonderful because

I love, I love the SAMMA product.

I mean, we were, we were preserving the world’s history, you know, the, the National Archives

and Library, the Library, US Library of Congress, the Shoah foundation, the, you know, criminal

tribunal in the Rwandan genocide from the UN, like just history.

So anyway, I digress.

Chris Lacinak: 23:07

Well, no, I mean, actually the last step, as we sit here today and talk, the last episode

that aired was with the video of Fortunoff, the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, which was, I think one of the first, if not the first SAMMA users.

So that, that definitely ties in.

s that around, I think it was: 2015

maybe: 2016

I remember wandering around the NAB floor and, and for the past several months had been

having conversations with Indiana university about this concept of a project around, you

know, this, this, they, they had just digitized or actually were in the process of digitizing

hundreds of thousands of hours of content, video, film, audio.

And they had the problem that they had to figure out metadata for it.

You know, they had some metadata in some cases, in other cases, they didn’t have any, in other

cases it wasn’t dependable.

So we, we were working on a project that was how does Indiana university and others tackle

the challenge of the generation of massive amounts of metadata that is meaningful.

And so we, that, that was the spawning of this project, which became known as AMP.

And by the time this episode airs, we will have aired an episode about AMP, but I was

wandering around the NAB floor.

I come across GrayMeta.

As I remember, it was in like the backup against the wall.

And and I’m like, Oh my God, this is the thing we’ve been talking about.

Like it was kind of like this amazing realization that you know, other folks were doing great

work on that front as well.

I think at the same time there was maybe Perfect Memory.

I mean, they’re, they’re one of the ones who I see doing metadata on the timeline and in

a kind of a similar way that you’re talking about, but but yeah, there weren’t, there

weren’t a lot of folks that were tackling that issue.

So it’s really cool one to have seen the evolution.

Do I have that timeline right?

Was it about like: 2015

Was that you had a product at that point?

I remember seeing it.

So like you had been working.

Aaron Edell: 25:08

Yeah, so I, so we, I joined, I was, like I said, the second employee at GrayMeta, which

would have been August of: 2015

Right.

It must have been.

Chris Lacinak: 25:23

Yep.

Aaron Edell: 25:24

Yes.

So we, we did have a big booth and we had a product, but it’s possible. I can’t remember exactly when it is we introduced machine learning for the tagging is possible.

It was by then.

Yeah.

But it wasn’t right away that originally we were just scraping exif and header data from

files and, and sort of putting a, putting that in its own database, which yeah, it’s

cool.

It’s useful.

But when, when machine learning came out, holy cow, I mean just speech to text alone.

Yeah.

Think of the searchability.

Yeah.

s was definitely a problem in: 2016

so for many years was that your only option was to use the machine learning as a service

capabilities from the hyperscalers and they were great, but they were very expensive.

Chris Lacinak: 26:13

Yeah.

Aaron Edell: 26:14

And talk about like cost optimization.

You know, we would even as testers, we would get bills from, from these cloud providers that, that shocked us after running it, running the machine learning.

So we, it’s why we started Machine Box was because it just, we just didn’t think it had

to be that, that, that that was the only way to do it.

And, and it was a problem.

Like we were having trouble getting customers because it was just too expensive.

That’s all been solved now.

But, but that’s why I think this is why it’s interesting because the, the, it’s really

good validation that you guys, that other people had come up with the same idea.

That to me is a great sign.

Whenever I see that when independently different organizations and different people kind of

come to the same conclusion that, yeah, this is a problem.

We can solve it this way.

But I think it’s taken this long to do it in a way that’s affordable, honestly, and

secure.

And also the accuracy has really improved since those early days.

Chris Lacinak: 27:15

Yeah.

Aaron Edell: 27:16

It’s gotten to the point where it’s like, actually this, I can use this.

This is a pretty, the transcripts in particular are sometimes 90 to 99 to a hundred percent accurate even with weird accents and in different languages and all sorts.

Chris Lacinak: 27:29

Yeah.

I agree. It’s, it’s, it’s, it’s come a long way to where it’s, it’s production ready in many

ways.

Let me ask you though, from a different angle, from the, from the customer angle, do you,

what are your thoughts on whether consumers are ready to put this level of sophistication

to use?

What do you see out there?

Do you see wide adoption?

Are you struggling with that?

What’s that look like?

Aaron Edell: 27:54

So do you mean, you mean from the perspective of like, Hey, I’ve got a Dropbox account or something and I want to, I want to process it with AI?

Chris Lacinak: 28:01

Well, I think there’s, I think about it in a few ways.

One is, are people prepared? And here let’s think about logistics and technology.

They have their files in a given place.

They know what they know, what they want to do.

They can provide access, they can do all those things.

But the other is kind of policy wise, leveraging the outputs of, of, of something like Wasabi

AiR to be able to really put it to use in service of their mission and providing access,

preservation, whatever those goals are.

Do you, I guess I’m wanting readiness on both those fronts.

Do you, do you see that as a challenge or do you find people are diving in whole hog

here?

What do you think?

Aaron Edell: 28:40

I think, I think people are diving in.

I think we’ve really reached the point now where I do think it’s kind of, it’s a combination of the accuracy and the sort of cost to do it.

Because if it’s not very accurate and very expensive, that’s a problem.

If it’s very accurate and very expensive, it’s still a problem.

But but we’re at a point now where we can do it inexpensively and accurately.

And so I’ll mention that even just today, which, which, you know, by the time folks

listen to this, it’ll probably be a few weeks in the past now or so.

But Fortune magazine published a post about Wasabi AiR and the Liverpool Football Club.

And they, what I, what I love is that they make it very clear, right?

Their use case, which is we want our, the fans of the football club to be able to go

onto an app and just watch highlights of, you know, Mohamed Salah crushing Man U, right?

Manchester United.

And just get it like a quick 30 second compilation of like all the goals or whatever, you know,

just just fan engagement.

And in order to accomplish that, you know, Liverpool has unbelievable amounts of video

content from every game from multiple cameras.

They’re, you know, they’re, I think people imagine that there’s there’s like a whole

bank of editors sitting around with nothing better to do.

It’s not really true.

They don’t, they don’t have that many editors.

And these editors have to, you know, create content from all of this library and archive

constantly and based basically Wasabi AiR makes them do it so much faster that they

can actually have an abundance of content ready for their app, which helps with increases

fan engagement.

And it’s that simple for them.

And they like the quote in the article from Drew Crisp, who is their senior vice president

of their digital world, says that that’s how they think about applying AI.

You know, we want to solve this use case.

We want to be able to create this 30 second compilation of all these goals.

Maybe it’s against a specific team or whatever the context is.

But we can’t sit around for hours and hours and hours watching every single second and

maybe manually logging things or tagging things or, you know, it’s always like, it’s always

a, it always happens after the fact, right?

You’ve recorded it all.

Okay, now it’s on a, it’s safe on, it’s on a disk.

I’ve got all my footage.

And then maybe you, you know, you in the file name, you put the team you played, but that’s

not enough metadata.

So, yeah, so I think they are ready.

I think, you know, it’s, it’s, um, people have to think about it the right way.

You know, this is a productivity boost.

This is a time-saving boost.

This is a, what hidden gems do I have in my archive boost?

You know, that latter, that latter use case, by the way, is, is really spectacular, but

very hard to put a number to and hard to measure.

You know, how much money do I make from the hidden gems?

The things that I didn’t even know I had in the first place.

Chris Lacinak: 31:57

And I, and sports organizations are interesting.

They’ve always kind of been at the leading edge, I think when it comes to, um, creation and utilization of metadata in service of analytics, statistics, fan experience.

I mean, we think about Major League Baseball was always doing great stuff.

NBA has done some great stuff.

I mean, it’s, and, and they have something going for them, which is a certain amount

of consistency, right?

There’s a structure to the game that allows there’s, there’s known names and entities

and things.

So, um, so that does make a lot of sense.

And it seems like it’s just ripe, uh, for, for really making the most of something like

Wasabi AiR.

I can just see that being a huge benefit to, to organizations like that.

Um, are you seeing, can you give us some examples?

Are there other, um, maybe non-sports organizations that are, that use cases that are using Wasabi

AiR?

Aaron Edell: 32:53

Yeah, definitely.

Um, I’ll give you one more sports one first though, because there there’s, you know, the, the use case I gave you is, is about creating content and marketing content for channels

and for consumption of consumers.

But they also are, you know, especially teams, individual teams are very brand heavy in the

sense that they, you know, they seek sponsorship for logo placement in the field or the stadium

or whatever.

And AiR is used for, by sports teams to look at that data and basically roll up, hey, the

Wasabi logo appeared in 7% of this game and the Nike logo appeared in 4% of this game.

And then you can go to Nike and say, Hey, do you want to be 7%?

You should buy this logo stanchion or whatever.

So really interesting use cases there, but non-sports use cases.

So one of my all time favorites is a, uh, a company called, uh, Video Fashion and Video

Fashion has a very large library.

I think it’s on the, to the tune of 30,000 hours of video footage of the fashion industry

going back as long as video can go back.

And they, um, and, and a lot of this was on videotape and needed to be digitized.

And I think they still have a lot that still needs to be digitized, but they used Wasabi

AiR back when it was called Curio, um, basically to kind of, you know, auto tag and catalog

these things so that when they get a request for, and they licensed this footage, right?

So this is how they make money.

This is how they monetize it.

This is why I like this use case because it’s a very clear cut monetization use case where

they sell the, you know, they licensed this footage per, I want to say per second probably.

And they, and so Apple TV Plus came to them one day as just an example and said, Hey,

we’re making a documentary.

It’s called Supermodels.

Do you have any footage of Naomi Campbell in the nineties?

It took them like five seconds, right?

To bust out every single piece of content they have where not only does Naomi Campbell

appear, but her name is written across the street.

Somebody talks about her, right?

So it, it’s literally like a couple seconds.

Yeah.

And then they just, they license it, right?

So they, they get all this revenue and have very little cost associated with servicing

that revenue.

And that’s exactly the kind of thing we want Wasabi AiR to empower.

You know, it’s time is money, my friend.

Yeah.

We’re saving time.

Chris Lacinak: 35:21

I love, one of the things I really like about Wasabi AiR is that it allows you to do sophisticated

search where you can say, I want to see Naomi Campbell. I want it in this geographic location.

I want it at this facility and wearing this color of clothing or something, right?

Like you can put together these really sophisticated searches and come up with the results that

match that, which I think is just fantastic.

I think that is, that is the realization of what the ideal vision is for being able to

search through audio visual content in the same way that we search through Word documents

and PDFs today.

I mean, that’s, that’s, that’s fantastic.

I’d love to dig into like, let’s dig, let’s make this a little bit more concrete for people.

We haven’t really talked about exactly what it is.

We’ve got this high level description.

But let’s jump in a little bit more.

So, so folks that are going to use Wasabi AiR would be clients that store their assets

in Wasabi, in Wasabi storage.

Is that a true statement?

Aaron Edell: 36:15

Yes, they, they can be existing customers or, you know, new customers. But yes, you need to, you need to put your stuff in Wasabi storage.

Chris Lacinak: 36:23

You’ve got your assets in Wasabi storage.

How do you turn Wasabi AirRon? Is it something that’s in the admin panel?

How does that work?

Aaron Edell: 36:31

Not yet.

I mean, that is, that’s where we’re working towards. Right now, you reach out to us, you know, reach out to your sales representative or,

you know, honestly, on our website, I think we’ve got a submission form, you say, I’m

interested, this is how much content I have.

And you don’t have to be a Wasabi customer when you reach out, right?

Like, we’ll help you sort that, sort that out.

But essentially, when we will, we’ll just, we’ll create an instance for you of Wasabi

AiR.

And when we do that, we’ll attach your buckets from your Wasabi account, and it’ll start

processing and basically, you’ll get an email or, you know, probably an email with a URL

and credentials to log in.

And when you click on that URL and log in, you’ll have a user interface that looks a

lot like Google, right?

It’s, it’s, there’s, you know, some buttons and things on the side, but essentially, right

in the center is just a search bar.

And we want it to be intuitive, of course, obviously happy to answer questions from folks,

but you should be able to just start searching, you know, we’ll be processing the background

and maybe you want to wait for it to complete processing, it’s up to you, but you can just

start searching, and you’ll get results.

And those results will sort of tell you, you know, some some basic metadata about each

one, there’ll be a little thumbnail.

And then let’s say you search for the word Wasabi.

And maybe you specified just logos.

I just want where the logo is a Wasabi, not the word or somebody saying Wasabi.

When you get the search results, let’s say you click on the first one, you’ll have a

little preview window and you can play the asset if it’s a video or audio file, right?

We have a nice little, you know, proxy in the browser.

And then you’re going to see all this metadata that’s all time line, timecode accurate along

the side.

And you can kind of toggle between looking at the speech to text or looking at the object

tags, and then on the bottom will be a timeline kind of like a nonlinear editor, be this long

timeline and your search term Wasabi for the logo, you’ll see all these little like kind

of tick marks where it found that logo.

So you can just click a button and jump right to that moment.

And what I like about that is so let’s say, let’s say in the use case, you’re trying to

you’re trying to quickly scan through some titles for bad words, or for nudity or violence

or something like that.

Those, you know, those things will show up and you can just in five seconds, you can

just, you know, make go through them and make sure they’re either okay or not, right?

Like sometimes, for example, it’ll, you know, it’ll give you a false positive.

That’s just what happens with machine learning.

But it doesn’t take you very long.

In fact, it takes you almost no time at all to just clear it and just, you know, go through